Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Editorial Opinion | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

(double-click any word to see its definition)

When I was twelve I awakened to the larger world, and discovered — girls? No, that came later, and if the truth be known, that was anticlimactic by comparison. No, I stumbled on amateur radio — a hobby that (then) involved days and weeks spent building and operating radio transmitters and receivers.

Many years later I sorted out what I had actually discovered (that nature is much more demanding, even-handed and truthful than any person can hope to be) but at the time, being twelve and congenitally lazy, I dwelt on the small, easily accessible facts — the low-hanging fruit. I discovered I could dismantle a broken TV set and reshape its parts into a radio transmitter. Then I could string a wire through nearby trees, feed it with the energy from my transmitter, and (if anyone cared to listen) my signal could be heard thousands of miles away.

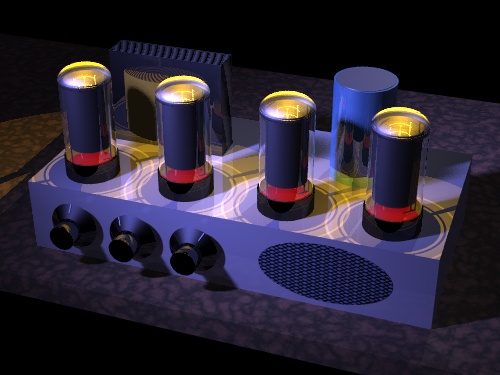

Surrounded by glowing vacuum tubes, isolated from the corporeal world, I would type out contentless messages with my telegraph key. Most likely no one was listening, but the idea that my signal could be heard at some fantastic distance gave me what I really wanted — vicarious escape. Trapped in suburbia, I imagined surfing away on radio waves.

One day I realized I could listen to my primitive home-built radio as I walked to school, but only if I carried a stick with a large square piece of metal attached to it, to pick up the radio waves. I was so completely immersed in my private world that I had no idea how I looked, walking along, carrying what must have looked like a metal protest sign. I was certainly protesting something, but I had no idea what, so in a weird way the blank metal sign was perfect.

I was a complete misfit, and because of my age I thought that was important. I was utterly unlike the people I knew — successful, normal people, people who absorbed the evening news before falling asleep. I hated school, regarded it as a kind of prison with no possibility of parole, and I did all I could to minimize the time I wasted there. While in class I drew diagrams of radios I would build if only more of my neighbors' TV sets would expire, after which I would inherit their lifeless hulks.

I lived in an isolation so perfect that I am still astonished by it. I raised escapism to an art form, the only option being which fantasy world I escaped into. My outward demeanor was so flat, so lacking in social responsiveness, that I was widely believed to be a dullard. The well-meaning teachers, noting my dropout status and indifference to nearly everything, tried to move me into a class for slow learners. But then an I.Q. test, required for this change, ruined everything.

Don't take that too seriously — in fact it has taken my entire life to learn what I desperately needed to know when I was twelve, therefore in truth I'm not so smart, and I.Q. tests are notoriously inaccurate. In the evening hours I would sit in a dark room, lit only by the glow of filaments from my vacuum tube radios, listening to distant voices, typing out Morse Code on a telegraph key, believing there would always be vacuum tube radios, and there would always be a place for what I had learned by age twelve.

As it turned out, vacuum tube technology had a rather short life, and in retrospect it seems to have been doomed from the start (because vacuum tubes essentially cook themselves to destruction). Tubes were replaced by transistors, and they in turn were replaced by integrated circuits — just in a period of 50 years. The history of electronics is a series of transitions, one thing replacing another based on overwhelming and obvious superiority, but the point this article makes is that everything is a series of transitions, now and always. And the most successful people are those who accept, and adapt to, constant change. This adaptability requires a degree of flexibility and humility most people can't manage.

In modern times, very little of what we learn about the world can survive even 50 years of persistent research. It is entertaining to read the history of human knowledge and see how many ideas had to be abandoned along the way. We once believed the universe was a system of concentric spheres, with the Earth at the middle of course, surrounded by one set of spheres carrying the planets, more distant spheres with the stars somehow pasted on, all revolving by way of a celestial clockwork.

It involved a great deal of mental anguish, and some outright murders[1], just to displace the Earth from its assumed position at the center of everything, much less to begin to understand anything about the universe outside of dogma. Then, after a small bit of progress, light waves were thought to travel through something called the "ether", sort of like how water carries water waves from one place to another. Then an experiment pretty much disproved the existence of the ether, after which Einstein came along and replaced the ether theory with a more robust explanation, one better able to stand up to experiment, but a bit more difficult to understand.

During the past ten years most of that certainty has been dashed again, and it turns out the universe is composed primarily of matter and energy of an unknown kind, not explained at all by existing physical theories. According to recent observations, this so-called "dark matter" and "dark energy" comprises 96% of all mass-energy, which means, based on a crude measure of quantity, we've hardly begun to sort out physical reality.

Or, to put it succinctly, our assumptions about the universe have been swept away.

For the past several hundred years we've been learning how to use the methods of science to examine the world and shape our theories about it, with good results. Science, contrary to popular belief, is not a system for moving gradually from uncertainty to certainty, but instead is a way to formally challenge any prevailing theory. There are no ultimate truths in science, only theories that haven't been shattered yet. This makes science a perfect tool for a world of constant change.

Here's another example from the field of cosmology. Around Einstein's time, the universe was thought to be relatively unchanging, a constant, reliable background for events on Earth, but that illusion is now shattered. It turns out the universe started about 14 billion years ago (for my British readers, that's 14 * 109 years) in a cataclysmic explosion, and has been expanding ever since, according to a theory called the "Big Bang".

After observational evidence accumulated for the Big Bang and made it seem likely, some cosmologists argued that the universe might eventually collapse again and maybe start over with another Big Bang, which restored a kind of permanence to what otherwise would be constant, patternless change. Unfortunately, according to the new dark energy theory, it turns out the universe will probably expand without limit, with no cycles and no repeats, gradually becoming colder and darker.

Swept away.

About the turn of the last century, Freud and some of his students tried to create a science of mind, a systematic, evidence-based approach to explaining human behavior. Part of this program was the idea that very serious mental conditions could be alleviated, even cured, by sitting around and talking. This weird idea took hold, primarily based on wishful thinking, and even in the present there are some poorly educated people who still think you can talk people out of crazy behavior. But as time has passed, more and more of the conditions described by Freud and his students turn out to have causes beyond the reach of conversation. Some of these conditions yield to various drugs meant to replace crucial (and absent) precursors for normal mental processing, and some respond to surgery.

Contrary to another popular misconception, science has had very little influence on the field of human psychology, as a result of which it will be decades before people realize that talk therapy doesn't work, in the sense that it doesn't have any remedial properties apart from the simple pleasure of conversation. In the meantime, more and more mental conditions will be discovered to be organic in nature, and more will be discovered to be curable by something more akin to conventional medical treatment than popular hand-waving psychological theories about how one was twisted by one's parents. And some will never be curable, except by what is euphemistically described as "genetic counseling."

But in the final analysis, because this all depends on a human brain trying to analyze itself, we will never fully understand ourselves while using our own brains as the instruments of research (in the sense proposed by the creators of the field of human psychology). Someday we might create a computer so far beyond our own abilities that it might offer us some insight into ourselves, just a few minutes before it takes control of the world.

But there is one thing I am sure of, in all this. In spite of our irrationality, our mercurial reactions to life, our inability to sit at peace, there is one justification for our "design". And that is the possibility of a catastrophic change in our environment, one that destroys all the creatures whose behavior is genetically hard-wired. And after the next giant asteroid collides with the earth, when the earth cools down (or warms up, depending on the details), I think I know which species will crawl out alive.

Swept away.

About 1913, in a famous work named "Principia Mathematica," a title borrowed from Isaac Newton, Bertrand Russell and Alfred Whitehead attempted to prove that mathematics derives entirely from strict logical principles, without uncertainty or ambiguity. This work was the culmination of a traditional outlook in science and philosophy based on the idea that all of nature could be observed and understood, with no room for doubt or uncertainty.

The ink was scarcely dry on this encyclopedic work when its premise was shattered by the work of Kurt Gödel, who proved (in his "incompleteness theorems"[2]) that all logical systems above a certain complexity level were unable, by virtue of self-reference, to prove some of their own assertions. The legitimacy of Gödel's proof gradually became apparent to everyone, and projects like the Principia Mathematica were seen to be irremediably flawed.

Gödel's work is not for the faint of heart, but a simpler logical conundrum can be stated in a few words, one that belongs in the same class. Let's say there is a library that contains all of human knowledge. Because we would like to gain access to the library in a more orderly way than by wandering the aisles, we decide to create an index of the library's contents. We succeed in creating the index, which is judged to be perfect on the ground that it contains a reference to every work in the library. Then someone points out there is one book the index doesn't list, and that doesn't occupy a place in the library — the index itself. To accommodate the first index, a new, larger index is constructed that includes the first index, but that suffers from the same problem, ad infinitum.

Swept away.

According to a scientific philosophy referred to above, one commonly heard before the turn of the last century, if only we could observe every particle in the universe, take note of their positions and velocities, we could predict the history of the entire universe. What we now call the "butterfly effect," the idea that there are natural conditions able to greatly amplify the consequences of a very small initial event, was of no consequence, as long as we were able to locate that particular butterfly.

Then, beginning in the 1920s, scientists responded to new observations by creating a theory unmatched for sheer weirdness, but that has stood up to experimental tests, indeed it is one of the best-supported theories in the domain of science. Called "quantum theory," it suggests there is an unavoidable uncertainty built into nature, and therefore predicting the future, in any but a broad statistical sense, is quite impossible.

According to quantum theory, the only reason we think we live in a predictable world is because large collections of particles obey statistical rules that individual particles do not. Another way to say this is the uncertainty in the position of a large object is proportional to the reciprocal of the number of particles that compose it. So large objects have a predictability in position and velocity that individual particles do not.

The key to this idea is that large objects obey the summed, average statistics typical of large masses of particles, but individual particles show much more uncertainty. A simple example is to say that, if you flip a coin a million times, the average of all the flips (counting heads as one and tails as zero) is extremely likely to lie near 0.5. But for any single coin flip, the probability of the 0.5 result is zero — it can't happen.

In quantum theory, and in laboratory experiments, the behavior of individual particles is quite astonishing. It is not an exaggeration to say that a particle that is not being observed has no conventional existence, as we understand that term. Its mass-energy will eventually be accounted for, but where it is, and how fast it is moving, can only be resolved by observing it.

In one now-classic experiment[3] meant to show the wave nature of light, a plate is prepared with two vertical slits to allow light through. Some light passes through one slit, some through the other, and at the target on the other side, the light beams combine in an interesting way — because of the geometry of the experiment and the travel times required to get to the target, sometimes the two light beams combine to increase the brightness of the light and sometimes they destructively interfere, creating a dark region. This is called an "interference pattern," one familiar to physics students.

As the implications of quantum physics became apparent, someone argued that the longstanding question of whether light consists of waves or particles could finally be resolved. An experiment was arranged in which fewer and fewer particles were allowed into the interference apparatus. The expectation was that, as the number of particles decreased, a point would be reached where the interference pattern would disappear, because there would be too few particles for even one particle to pass through each slit.

This experiment was the point at which the truly spooky nature of quantum theory became apparent to everyone. It turns out that, even if only one particle is released into the experimental apparatus at a time, that single particle never lands on the dark parts of the original interference pattern. The explanation for this result is that the particle is only a particle while it is being observed, but the rest of the time, it exists as a field of probabilities. Because there is equal probability for the particle to pass through slit A or slit B, it passes through both simultaneously. Consequently, when it gets to the target and becomes a particle again, it will have interfered with itself, and will never land in the dark parts of the pattern.

There are some special circumstances in which a single particle's uncertainty can govern a large event. The classic example of this is called "Schrödinger's Cat,"[4] and it goes like this. A cat, a radioactive source, a Geiger counter, and a blasting cap are all sealed up in an enclosure. The box is closed up so no observer can see the outcome (except the cat, who for reasons unknown isn't counted as an observer). There is a certain probability that the radioactive source will release a particle, which will trip the Geiger counter and set off the blasting cap, killing the cat. Let's say the probability that the cat remains alive after fifteen minutes is 50%.

In classical physics, after fifteen minutes, the cat is either alive or dead, and we can determine the outcome by opening the box. In classical physics, the result is independent of observation.

In quantum physics, until the box is opened, the cat is neither alive nor dead, but exists in a superposition of states that can only be resolved by observation, just as with the single particle in the two-slit experiment above. The cat is neither alive nor dead until the box is opened.

There are some problems with this famous example that would prevent it from actually being carried out, but the underlying idea is quite valid — there are events governed by quantum probability that can have macroscopic consequences. For example, it is now widely held that we are approaching the limits of prediction for weather forecasting because of this "butterfly effect" — small initial effects, within the realm of quantum uncertainty, can and do have large consequences, and they will prevent much more improvement in our ability to predict the evolution of weather patterns. So much for knowing if it will rain this weekend.

Swept away.

This section makes two points. One, much of what we thought we knew 100 years ago has had to be discarded, requiring us to learn new things not taught in school. Two, what we are discovering is that nature is less predictable than we assumed, a discovery that requires us to rely more on intellect and less on instinctive patterns of behavior.

Which leads to a question: Are students being educated for the world of the present, or one we left behind 100 years ago?

It turns out that modern public education cannot prepare students for a world of constant change. In fact, the argument is often made that what we call education is instead a largely successful effort to extinguish the single most important adult survival tool — a natural curiosity about the world. Those for whom modern education is a perfect fit are ill-prepared to survive outside the classroom, and the fact that this is so suggests public education must serve some purpose other than optimally preparing students for reality.

And — no surprise — it seems public education's true purpose is to force docility and a herd mentality onto students, to make them harmless, obedient, and predictable. Anything the students learn along the way to this outcome is coincidental to the main purpose. It would be easy to point fingers and assert (as many have done) that it is government, public education's primary source of funding, that engineers this outcome, but in truth it's hard to decide whether government or parents want this outcome more.

I've never been a parent nor had any impulse to become one, and on that ground my views on parenting may be thought either priceless or totally without value, depending on the reader's perspective. After a lifetime spent observing parents, it seems to me that parenting is a contest between what the parents want — a smaller version of themselves — and what nature wants — something never seen before. In the long term, nature wins this contest.

When I say "nature", what do I mean? Isn't biological reality a brutal contest to see who doesn't die, in a morally neutral universe? Well, yes, but pay attention to who survives, because that can be defined as what nature intended (not to ascribe any conscious intention to the process). This is the harsh reality into which all those students are released after graduation, and coincidentally this picture corresponds to one of the better-established scientific theories, evolution.

A digression. Have you wondered, as I have, why religious people object so strenuously to the theory of evolution? At first glance, it seems that a very old planet Earth, and constantly changing species, any one of which might come to dominate the others, confronts a literal reading of the Bible, so religious people object to it on that ground. But a less superficial look reveals that evolution argues for a world of flexible rules and constant change, and religion argues for fixed rules and no change. The central idea of evolution is that everything we see around us — all knowledge, all social institutions, even the notion of a central role for human beings — is a detail in a larger pattern, a momentary state in an ever-changing story, and that idea produces profound unease among religion's natural constituency. If people are merely an experiment conducted by nature, if life must constantly adapt to a changing world, then every city (and every church) is built on shifting sand.

In a sweet irony, the single trait of greatest survival value in a changing world, the trait that humans possess to a higher degree than most other animals, is intelligence. The primary value of intelligence is that it can produce a new adaptive behavior without relying on evolution's strategy, that of killing off everything that can't adapt. This is ironic because intelligence is a very fast way to adapt to change, but it produces remarkable staying power in the species that possesses it.

Another irony is that parents create children in two equally important ways — biologically and intellectually — and the primary role of parents after a rather early point in their childrens' lives is to transfer a personal intellectual package at least as important as the personal biological package delivered through genetics. But a combination of obedience and laziness causes most modern parents to turn their children over to public schools for this crucial stage of their development. It turns out that public schools, focused as they are on unchanging rituals and patterns of behavior, are more consistent with the older biological way of producing a particular outcome (everyone who doesn't fit in dies, either spiritually or literally).

All these points may be reasonably argued, but there is one point on which most people agree — public schools are not meant to teach people how to think, instead they deliver fixed content, lists of facts, in much the same way that genetics delivers a set of inflexible traits. If public schools changed, if they trained students to do their own original research and decide for themselves what was true about the world, governments would immediately withdraw all support, the entire system would collapse, and children would have to sort the world out for themselves, just as they did before this remarkable system was created.

The sublime moment of victory for modern education is also one of surreal confusion when a typical student says, "I've graduated. My education has ended." But education never ends. In a small sense, it doesn't end because most of what my generation learned in school is now known to be wrong, a pattern that will likely repeat each generation. In a larger sense it doesn't end because survival means learning new things forever. But according to the educational system's priorities, a student's education ends on a particular date, and the earlier that date, the better, because the goal of modern education is, not a village of human beings, but a flock of sheep.

In the entire sweep of human history, there has never been a time like the present. Now that we have permanently unseated religion and other systems of fixed belief as our primary way to interpret reality, we are discovering many amazing things about nature and ourselves, some encouraging, some disturbing.

We once believed the earth was a permanent, stationary object in a permanent, stationary universe. We now know this is untrue — the earth is a spacecraft moving through the universe, and eventually (in about five billion years) the sun will expand and consume the earth[5].

We believed the universe was unchanging, static. We now know this is untrue — the universe started with a Big Bang, and recent discoveries suggest it will continue to expand, creating a cold, dark future in the long term (as explained more fully here).

We believed that physical reality was ultimately based on complete predictability, and that we might understand and predict nature perfectly if given the proper theories and instruments. We now know this is untrue — because of its quantum foundation, nature is unpredictable in all but the most superficial ways.

We believed mathematics and logic could replace the now-discredited system based on religion and superstition, providing an equal measure of certainty, but based on testable ideas, not mere belief. We now know this is only approximately true, and for some kinds of questions, mathematics and logic contain inherent limitations[6].

When facing these new discoveries and their implications, intelligent people may conclude that the old focus on fixed beliefs should give way to a focus on individual choices and individual accountability. If we can't safely ally ourselves with a fixed system of beliefs in a fixed world, we can instead educate ourselves to the point that we are able to make appropriate personal choices based on personal values.

In the old system, replacing a religious leader's guidance with personal choices was regarded as dangerous and selfish. Now the logic has been reversed — we now realize nothing is more dangerous than unthinking obedience to a discredited institution.

A well-known debate has it that free will is an illusion, that we are mere puppets in a biological play. This question is not resolved and, based on recent discoveries, may never be resolved to anyone's satisfaction. I think we need to proceed as though free will exists, on the ground that it's safer to assume it exists and accept personal responsibility for our choices than to assume it doesn't and act like powerless puppets.

The paragraph above recycles an old argument about religion, that it's safer to assume God exists than to assume he doesn't. Based on present knowledge, and based on how much trouble religion has caused, I think it's high time to reverse this old argument. Instead of assuming that religion and other fixed belief systems have anything to offer us, we should act on the assumption that free will exists, that individual choice represents the highest authority, and we should accept personal responsibility for the outcomes.

There is one more consequence to replacing obedience with personal responsibility, one that may not occur to some of my readers. It is one of many statements of the Symmetry Principle[7], and it goes like this: if we refuse to take responsibility for our failures, we lose the right to take responsibility for our successes.

Put very simply, it's time for us to act like grown-ups.

| Home | | Editorial Opinion | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |