Chapter 8 — Tel Aviv to The Caribbean

|

Overlooking a port in Cyprus

|

Larnaca, Cyprus was my first stop after Israel. It was one of those prosaic nautical experiences in which a particular town is supposed to have every imaginable kind of store and supply one could wish for, then when you arrive there is nothing.

I was told there was a sail maker in Larnaca, fortunately I decided to have my sails repaired in Tel Aviv, thinking, a bird in the hand, etc. There was no sail maker in Larnaca.

I was told there was a Yanmar Diesel dealer in Larnaca. I heard this as far back as Egypt. I made up a list of the parts I damaged during my makeshift repair, as well as all the spares one might wish to have. When I got to Larnaca, I found the phone number of the "dealer." After some struggle, I discovered that he had no shop, no parts, and no knowledge. If you went to a particular place on a particular day, and he wasn't busy, he would be there too, and (if you brought your own part numbers) he would take your money, order the parts from Japan, then ninety days later deliver them to you and charge you retail. Even if I had wanted to do this I didn't have any part numbers, and I certainly didn't want to spend ninety days in Larnaca.

I delivered my life raft to a shop at the marina that advertised itself as being an inspection service. It turned out that the life raft inspection was carried out at a shop in another town (Limassol) whose schedule was very relaxed. I stayed an extra week trying to recover it.

On the bright side, a group of boat people and I rented some motorcycles and toured Cyprus. We planned to have eight people on four bikes. I thought it would be nice to have a big, comfortable bike, so I chose a Honda 650. If I had known how far I would be pushing it I would have selected a more modest size. The rental agency provided approximately one teaspoon of gas, just enough to propel me out of sight of the rental shop. I pushed the bike about 2 kilometers to a gas station and filled it up.

Later in the day the battery began to act up, so that the bike would stall if allowed to idle, and the electric starter wouldn't work either (on many modern bikes there's no kick start lever). So if I stopped at a light and didn't keep the engine revved up I would have to push the bike, jump aboard, and start it. Then (while I kept the engine screaming) my passenger would get aboard and we would dart off.

That night the bike died completely, probably as a result of my foolishly wanting to use the headlight. After a three-hour wait the rental shop brought a replacement bike, which, when unloaded from the truck, couldn't be started. A mechanic was called in and the bike was brought to life about midnight.

The rest of the group had by now gone to a monastery in the hills near the town of Pafos (named Agios Neophytos) which provides overnight accommodation for free (the guests are supposed to figure out that donations are accepted). I didn't really get to see the monastery that night, wishing only to fall asleep, but on waking I thought Scotty had beamed me up by mistake.

The monastery overlooks Pafos and the Mediterranean, but the buildings are so well constructed and beautiful that it is hard to decide which direction to look. Behind the modern monastery is an older section built into the face of a cliff. The entire site is absolutely clean, plants tended and watered — a place where sweat holds entropy at bay.

From time to time one saw a monk, say, watering a plot of flowers, or moving from one room to another, head bowed. It was unsaid but clear that we outsiders should not interact in any way with them.

I enjoyed the visit but finally I thought it a mistake to go there. I realized no donation could balance the negative effect of an invasion of eight laughing, motorcycle-riding, casually dressed tourists. When the cameras inevitably came out I wanted to object, but I realized the explanation would be very long-winded and probably produce more heat than light, so I didn't start.

The remainder of the trip consisted of rides through a landscape very reminiscent of central California as it might have looked 75 years ago, and several hair-raising episodes involving certifiably insane truck or bus drivers, and some equally nutty behavior on the part of the other motorcycle drivers. I kept falling behind because I didn't want to die nearly as much, or as soon, as the others. I always thought the reason for a big bike was to have a comfortable ride, not to see how fast you could pass a top-heavy truck full of live pigs on a narrow mostly-dirt road with a cliff on one side.

Today is June 1. I arrived here in Finike, Turkey (site of ancient Phoenicus) early this morning, after a two-day crossing from Cyprus. I had not intended to stop in Turkey but a number of people said nice things about it, so I've decided to include it. I'm glad I planned it this way because the wind has started blowing with gale force (gusts of 45 knots), and I reached this port just in time to seek shelter.

The exchange rate is 2600 Turkish Lira per U.S. dollar, which makes transactions seem peculiar for a while. I filled up my diesel cans and discovered they wanted 102,000 lira. At first I thought I was being raked over the coals, not able to make the conversion in my head, but when I got back to the boat it turned out to be two dollars a gallon — usurious but not criminal.

As usual, an expectation wasn't met, but this time it was a pleasant surprise. A number of people remarked on the formidable Turkish bureaucracy and the time it takes to clear into the country. I guess some changes have been made, also in this marina the taxi drivers know the routine. For about four U.S. dollars they zip you around to the various offices and do some interpreting as well. The procedure took about an hour and a half, which is much better than average for this part of the world.

I'm not crazy about the anchoring and mooring practices here in the Med. When I arrived this morning I decided to anchor away from the marina inside the breakwater instead of trying to slide between two boats. Later, as the wind picked up, all the local charter boats returned at once and tried to slip into their berths. Several collisions took place, mostly because the wind unraveled some well-intended maneuvers. You know it's bad when you can hear the hulls crashing together across the marina, and see masts whipping back and forth.

I'm not staying long enough to launch my inflatable dinghy with the outboard engine, so I rowed my hard dinghy ashore several times this morning for fuel and clearance, to the amazement of the local sailors, who travel between marinas and rarely use a dinghy. I am completely alone on the far side of the bay — I hope I find places like this elsewhere in the Med. I think the extra distance is worth it.

(June 5)

I have just spent a couple of days at a place called Kale Koy, an area dominated by a castle on a hilltop. There are two small towns separated by a bay. One has the castle above it, the other offers more shelter from the wind, and, since the wind was blowing 35 knots when I arrived, I chose shelter. The next day I hiked around the bay to the castle.

After I climbed the hill and sat down in the ruins of the castle, I tried to imagine who built it and why. I can't imagine building a castle as a weekend project, a fling — there must have been a group wishing to preserve their goods or lives against some other group. And, because of the forbidding terrain, the "other group" would have to arrive by sea. The castle has high walls and a very large inside area, but no internal buildings, so I guessed that during an attack the entire village temporarily took shelter inside the walls.

Beneath the castle's walls, Turkish girls row wooden boats between the village and the boats riding at anchor, offering scarves for sale. They are invariably dressed in bright-colored pantaloons and scarves, and they are invariably pretty. When they get done with you, you may or may not own a scarf, but your heart is certainly broken.

I have noticed the majority of the yachts here are German, so I am once again using some of the German I learned from Bob and Ursula. The Turks I meet are much more likely to speak German than English as a second language, so I find myself speaking German to the Turks as well as to the other boat people.

When I noticed this preference for German among the Turks I remembered a special relationship exists between those countries dating from the opening days of World War I. In August 1914 a German warship escaped its British pursuers and made its way to Istanbul, in a masterstroke of diplomacy that effectively allied Turkey with Germany, with far-reaching effects. The British pursuers, thinking more in military than diplomatic terms, couldn't figure out why the German ship was racing East instead of West. By the time they discovered the ship's destination it was too late, Turkey permitted Germany access to its ports and thus to the Black Sea, and Germany was able to attack Russia from an unexpected direction. The terrible waste of Gallipoli was a later attempt to undo this damage, and the British, looking for a scapegoat, sacked their First Lord of the Admiralty, a young man named Winston Churchill.

Today I am in Kas (pronounced "kash"), my last stop in Turkey. Kas is somewhat dramatic, even though it doesn't have a medieval castle. The earth rises almost vertically behind the town, and some sarcophagi (burial sites) are hewn into the cliffs very high above the town. When I saw these I thought it's one thing to accept that the departed have gone to heaven, it's quite another to carry them halfway up.

(June 17)

I have been on a two-day stop in Rhodes nearly two weeks now. I had been told there was a dealer for my auto pilot here, and, as usual, there is no dealer in any meaningful sense of the word. I thought I would just pick up some extra electric motors and return my two broken auto pilots to service.

A brief explanatory note: an auto pilot is the device that steers my boat through the water. Without an auto pilot I would have to sit and steer the boat by hand, a practical impossibility for more than about eight hours. The key mechanical element in the auto pilot, and the part the wears out fastest, is a small electric motor worth about US$10. The entire auto pilot costs US$800.

It turns out that the company that makes the auto pilot won't provide spare parts. I had heard a rumor to this effect but I couldn't believe a company would hold their customers in such contempt and manage to stay in business. But it's true: if something breaks, you may (1) return the unit to England for repair, or (2) buy a new auto pilot. Option (1) would make sense if I wasn't sailing anywhere for six months. Option (2), which I am now exercising for the fourth time in three years, should be easy but isn't. The first marine store I approached was a dealer for my auto pilot — but in name only. They had no auto pilots, no catalogs, and no knowledge. They were willing to take my money and order a unit from England, then charge me higher than retail price. Reminded of the Yanmar "dealer" in Larnaca, I declined.

The second dealer assured me that there was an auto pilot like mine in Athens, it would be simply a matter of getting it from Athens to Rhodes, at which point in the conversation he couldn't resist saying "it will be here tomorrow." That was almost two weeks ago. It turns out the Greek Customs people are responsible for delivering things between the islands, to prevent anyone circumventing either the import duty or the 13% value added tax by shipping something directly to one of the islands and claiming it as a shipment within Greece.

But the Greek Customs people get paid the same salary whether their packages arrive on time, or late, or never. As a result late arrival is dearly to be hoped for, because on time almost never happens, and never almost always.

A friend, a more experienced sailor, used a different method. He called a vendor in the U.S., placed his order and requested air freight shipment. When he told me his plan I thought it was the silliest thing I had ever heard: an item from a company in England, about a thousand miles from here, is flown halfway around the world to the U.S., taken off one airplane and put on another, again flown halfway around the world to here, where it miraculously appears at the local airport's freight window, marked with the magic words "Spare parts for yacht in transit," to avoid problems with Customs. When I ridiculed my friend's plan, he looked at me with an expression normally reserved for brain-damaged children. He got his parts and left a week ago.

Rhodes is a pleasant enough place, apart from the artificial anxiety brought on by owning a boat. At one time there was an enormous bronze statue of Helios the Sun God that is said to have straddled the port entrance. Called the "Colossus of Rhodes" and counted among the wonders of the ancient world, it unfortunately was knocked down by an earthquake in 227 B.C.

A large, imposing and very charming castle dominates the skyline of Rhodes. Naturally this well-defended structure inspired people to attack it, in that adversarial logic for which humans are notorious. Principal among the attackers was Demetrius Polioketes, who fancied himself another Alexander the Great — we'll call him Demetrius the So-So. Anyway, he built a fantastic siege machine, nine stories high, weighing around 125 tons, that sheltered troops, delivered them over the castle walls, and catapulted huge stone balls against the defenders. Piles of the stone balls he used lie about the castle today — I tried to move one, and quickly realized I wouldn't be able to help Demetrius the So-So storm the castle. Later I did a little math and estimated that each ball weighs 360 kilos (800 pounds).

After I proved mathematically that I couldn't get the ball onto my shoulder, I sat down on it and thought about history instead. Someone once said that all history is lies. Certainly most of it is intended more to direct you to a particular outlook than to report events objectively, but even the comparatively objective parts tend to be swept away by the more dramatic events and people. That is why military history is dominated by battles in which many people got killed, regardless of their military significance. My favorite example is Douglas MacArthur's campaign against the Japanese during Word War II.

MacArthur used an interesting strategy against the Japanese-held Pacific islands: he would discover where the Japanese had most of their people and equipment, i.e., where they expected an attack, and he would leapfrog around that island to one behind it. He would attack this less-defended island, cut off communications and supplies to the more forward island, and the Japanese would have to abandon it.

The Japanese tended to be fairly rigid in their thinking, so MacArthur successfully used this strategy again and again. As a result he was able to keep his casualties down to about 60,000 men in a campaign lasting several years. By comparison, in Europe the Allies lost 100,000 men in The Battle of the Bulge, a single battle that lasted only a few weeks.

But history largely overlooks MacArthur's achievement — the casualty rate wasn't very high, therefore nothing important could have been going on out there. The effect of this kind of history is to plant the idea that you win battles by massed frontal assaults, an idea that should have been abandoned for all time in 1918.

The most dismal aspect of this kind of history, one reinforced every day in the evening news, is that ordinary people and events don't count. In the U.S., largely because of television and the realities of prime-time broadcasting, people who aren't famous aren't anything. A town will never be mentioned until a tornado rips it to pieces. A man will go unnoticed until he shoots up a schoolyard.

I have a story about this famous-or-nothing way of thinking, with a bit of "the only real poets are dead poets" mixed in. Once John Cheever gave a poetry reading, then opened up to questions and comments from the audience. One woman raised her hand and asked "Were those real poems or did you write them?"

(June 26)

The auto pilot never arrived in Rhodes and I finally left. A local sailor sold me an actuator, the only part I needed, so I think I have enough spare parts now.

After the town of Rhodes I visited Lindos, then Simi, and now Kos. There are many places in the Med with the same names — it becomes confusing. But there are other confusing similarities, like the many postcard-cute towns, each dominated by a castle. Lindos and Kos both have castles, parts of which predate the Christian Era. Simi had no castle, but in exchange it was picturesque and vertical.

Lindos is on the South coast of the island of Rhodes (not to be confused with the town of Rhodes) and its castle is spectacular. One gets the impression that every Greek town wanted to have the biggest, highest castle, and the original reason for the castles, to repel invaders, was forgotten.

I had heard nice things about Lindos, mostly having to do with the combination of architectural and human beauty one finds there. In the past it was a gathering place for young people, but now that overnight accommodations exist the average age is increasing. Lindos has more bars per square kilometer than anywhere I've yet visited.

Most beaches in Greece are topless in principle, many also in fact, some are bottomless as well. Some behavioral rules exist that are never spoken out loud but everyone understands. The first is the border between the taverna and the sand — on crossing this border one covers up or uncovers depending on direction of travel. The second rule is the same for nudist gatherings everywhere: no staring. Men being men, this second rule is obeyed reluctantly, and certain devices are employed to permit discreet peeking, or perhaps discreet staring might be more accurate.

One lazy day I sailed about the beaches of Lindos with my sailing dinghy, and saw many interesting things. At one place there was a nice flat rock area, away from the main beaches, perfect for sunbathing - but what's that? As I sailed closer I saw a row of older men sitting in the shade, each armed with a paperback book, facing the sunbathing area, um, reading.

Kos seems to have as many young people and bars as Lindos, as well as an international airport. According to some of the Europeans I talk to here, it is a preferred spot in the Greek Islands. Loud music in the evening, many people meeting each other.

When I sailed in I thought I would fill my tanks with water. Imagine my surprise when I found every water tap locked up! In Kos, ouzo is literally easier to acquire than water. I took my jerry cans ashore and prevailed on a sponge vendor to unlock his tap, which he graciously did. Later, wanting to show my appreciation and to assure a future supply of water, I bought one of his sponges. Then I wondered whether I might have insulted his generosity by seeming to pay him for the water. But I wanted to send a signal that yacht people aren't all exceedingly uncivilized and cheap, a general impression in the Med. I eventually realized the sponge man probably goes through the water-barter ritual every week and I was probably making too much of it. Besides, it's a nice sponge.

Now that I am in the Med I have been trying to behave like a regular person, in the hope of meeting people and defeating loneliness. I noticed some time ago that I feel a lot more lonely on land than while sailing — I think the proximity of people does it. So, since Mediterranean night life centers on bars, I go to bars. They are less sordid here than in North America, being mostly out in the open, with nice furnishings. Even civilized, a word I rarely apply to bars.

But let's face it, I am sort of a misfit in this environment. I make interesting conversation, a minor handicap. I am older than the fathers of about half the people I meet, definitely a major handicap. And there are some language difficulties, even though everyone knows at least some English. I can make myself understood in German, French and Spanish, but a normal conversation is out. I am the only American in town — there was one other but he sailed away.

I remain practical to the end. I expect to fill my evenings with conversation, but just in case I remember to take a book. If I'm not talking to anyone or walking around people-watching, I sit and read my book. Seems natural enough to me. I expect people to think "How interesting! Someone reading a book!" but sometimes I think the reaction is more like "Check out the geek with the book!"

I discovered something when I sat down to read the other night. The bar attendant came by and told me two things — one, to stay I had to buy a drink, and two, they had only alcoholic drinks for sale. I am the sort of person who will drink in company but I don't like to drink alone, so I walked around until I met someone.

Later I thought how peculiar that system sounded to an American. A combination of serious social problems brought on by alcohol in the United States and a tendency to sue anybody for anything, makes it necessary for bar owners to have coffee and other non-alcoholic drinks handy, and to stop serving people obviously drunk. But I haven't seen anyone ridiculously drunk here (maybe I haven't stayed long enough in bars or visited enough islands yet) so perhaps Europeans are more self-controlled than Americans would be in the same situation. I am quite sure if a group of Americans were exposed suddenly to this Greek drink-or-go-home system, they would be quickly reduced to a sodden, limp, incoherent, barfing pile of groaning bodies.

I recently fixed the computer system on the boat of some friends. The captain wanted to write letters and print them, he wanted to send and receive text messages over the radio, he wanted to be set up as Selene is, and he had all the necessary hardware. But the system had been installed wrong, it couldn't be used as it was, I was the only person who could do it. It took half a day and every test device I own, but I fixed the system.

I enjoyed the task, and my friends have a working system now. I thought about it later and was struck by the fact that I have a completely upside-down life: my work is my leisure, and my leisure my work. Taking care of my boat, deciding where I am going to go next, visiting the offices of government officials, protecting my boat from people who can't sail, this is work. Fixing somebody's electronic problems and then being invited to a great dinner, this is leisure.

I was to have sailed North today, but the wind has started to blow really hard, naturally from the direction I want to go. Oh well, I guess it won't kill me to have another sample of Med night life.

(July 14)

I feel as though I have visited every island in the Aegean. I have visited 11 places since Kos, most after motoring a small distance against the "Meltemi," a strong wind that blows from the North much of the time. After I visited Lesvos I got tired of beating against the wind (which seemed to be getting stronger), so now I am turning back South and using the sails again.

I seem to have adjusted to the summertime Aegean. I move the boat just often enough to maintain a kind of sun drenched rhythm of pretty places, whitewashed towns asleep in time, or bays of bright green sand. I have been dividing my time between towns, where one finds conversations, magazine stands and Greek salads, and isolated anchorages, where one recovers from the towns.

(July 18)

I am learning that the bigger towns should be avoided! I thought I would visit Mikonos to get fuel and water and to see whether the night life was as great as rumored. Even though the overall wind was moderate, the terrain at Mikonos produces gusts of hurricane force right in the marina. This is something you find out by going there, the guidebooks don't mention it. I managed to shred may favorite sail on the way into this "shelter."

But the fun had just begun. In the marina, people who chartered their boats three days before were bashing each other and the rocks, crossing up their mooring lines and anchor rodes, and generally making a mess. I took one look at the scene and departed, realizing that even if I succeeded in single-handing my boat into a mooring without hitting something, I wouldn't last two hours in there. There were twice as many boats as moorings — frustrated, inexperienced sailors motored in circles like sharks.

So I went up the coast about 5 kilometers to a small indentation in the coastline. It didn't deserve to be called a bay, it was just a place where the wind was blocked by a hill, and the waves were not quite as high as in the open sea. I anchored and got ready to make a fuel run in my dinghy. I put on my wet suit for this trip — there was no way I was going to make a trip in 60 MPH winds on the open sea without getting soaked.

It was the most miserable trip. Huge waves blew across the dinghy and me, and I could scarcely see for the spray. But I got my fuel.

Then I changed into dry clothes, beached my dinghy and took a bus to town — to arrive dry, you see. After all, the point of visiting a town in the Greek Islands is to sit down and have a Greek salad, and maybe get into conversation with people for whom a sailor is an interesting creature.

That evening, during just such a conversation, I kept being distracted by salt water that had been injected into my ear during my wild, wet ride and would probably require surgery to remove. I thought about my poor shredded sail — my favorite! — and how tired I was. But I kept this to myself, after all, I wanted to make sailing sound interesting, in which you cross an ocean without having to drink a good percentage of it. I didn't weaken and complain about my life on the sea, it was a nice conversation — I lied.

(July 22)

After two days in Ios I think it fair to say it is a pretty Greek island thoroughly spoiled by tourism. It has a reputation for free living and caters to the youngest tourists, a recipe for trouble.

As usual I declined to enter the marina, where people are packed porthole to porthole for the privilege of hearing disco music until 5 AM. I have anchored out in the middle of the bay next to the town, a good place to launch my wind surfer in the afternoon.

Ios is geographically divided — the old, "real" village is on top of a hill with a pretty cobblestone path called the "donkey trail" leading from the modern part of town up to the old village. And yes, donkeys still make their way up the path. All the nicer restaurants and bars are in the old village, in particular a place called "Club Ios," perched on the highest hill, best visited around sunset when they play classical music for the gathered sunset-watchers. On my first day here, sitting among the sunset crowd, I believed I was in yet another Greek island town where tourism coexists with traditional village life. But then the sun went down.

My version of a night on the town, an interesting conversation with interesting people, has no place in Ios. The probability of even a coherent conversation, much less an interesting one, floats near vanishingly improbable in the early hours of the evening, to later drown in a sea of alcohol.

From a philosophical standpoint Ios stands as an extreme embodiment of the human mating ritual. Young women, endowed by nature with an absurd perfection of beauty, appear at the beach in a spectrum of clothing that ranges between nothing and almost nothing. Young men, confronted by this sight, and surmising that it might be too good to be true, steel themselves with alcohol against the prospect of rejection before, during, and after visiting the town's public meeting places, which happen also to sell alcohol in many of its more lethal forms. At the height of the evening, people of both sexes, drunk, no, poisoned by alcohol, can be seen trying to steer their bodies from place to place among the narrow cobblestone paths, pausing here and there to throw up.

(July 25)

Thira is the site of a large island, the center of Minoan civilization, that blew up about 1400 B.C. and, according to prevailing theory, single-handedly destroyed that civilization. It is also coming to be recognized as the source of the Atlantis legend told by Plato.

The rim of a crater is all that remains, with a small central island of lava and ash that is still volcanically active, last erupting in 1926. The town of Thira is located high on the rim of the crater, so high that a cable car is used to lift people arriving by sea. The views are nice, both from the town at the top of the crater and at my boat, anchored at the bottom.

I hated leaving the boat at the anchorage because it is entirely open to the West, but I wanted to visit the town, so I put out two anchors. The town stretches along the rim of the crater and is perfect for touring on foot, which I did. After a long walk I had dinner with four American college-age women on holiday.

They saw me sitting alone in the restaurant and, being entirely modern women, invited me to their table. Fortunately for me they thought sailing was a highly romantic occupation, and they asked lots of questions. How did I find my way across the water? Did I see sharks and whales? Was it lonely out there? I don't know what impression I created, but they charmed me to death. They were smart, resourceful young women who had plans for themselves.

We then moved on to subjects besides sailing and I realized they knew something of the world — they weren't limited to conversation about Prince and Madonna. They wanted to know where I stood on abortion, the draft, gun control. And they were too classy to ask whether I was married or how I could afford to sail around the world. As the evening went by I stopped wondering whether they could prevail against the world and began wondering whether the world could prevail against them. They showed class and poise, and they broke my heart.

(August 2)

It may sound silly, but now that I have sailed away from Greece I realize more than anything else I am going to miss their salads. It speaks to the unpredictability of travel experiences that I will probably remember the salads longer than the donkeys or the cute fishing boats.

A typical salad served in a small Greek island town has tomatoes — lots of tomatoes — cucumbers, onions, bell peppers, olives, a slice of feta cheese, and a small bit of lettuce buried beneath. Usually everything in the salad is produced within 20 kilometers of the restaurant, so everything is fresh and there are local differences in content. But always great tomatoes.

To appreciate my enthusiasm for the Greek tomato, a tomato grown slowly and painfully in soil enriched with goat droppings, you would have to visit an American supermarket and sample the uniformly red artificial spheres offered there. You would also have to understand the place of salads in the American diet. In my childhood, salad was a punishment. If you were bad, if you were overheard saying a bad word or caught feeding the goldfish to the parakeet or vice versa, you got salad for dinner.

By "Salad" I mean a monotony of iceberg lettuce, perhaps broken here and there by a radish. Or a bell pepper. Which is why salad dressings are so elaborate in America — spicy, creamy, thick dressings, delivered in a bottle bearing a picture of someone famous, a meal in itself, can make even iceberg lettuce edible. By contrast, a Greek salad is dressed in the plainest way — oil and vinegar — so as not to hide its beauty.

In a Greek restaurant you are provided with small bottles of oil and vinegar, but it is understood that you will act responsibly. If you pour, rather than sprinkle, the vinegar, the proprietor may wither you with a stare. When I first arrived in Greece I acted toward a salad as a fisherman toward a fish — kill it, then eat it. But I have mended my ways. Would you grab a bottle of ketchup and attack an Italian chef's pasta and sauce? Okay, then.

(August 5)

Oh, my poor jib, my favorite sail. A sail that, when acting with greatest efficiency, also takes a pleasing shape. Torn from leech to luff now, lying in a disordered pile here in Malta. I have asked the sail person to assess whether these rips mean the fabric has lost its strength, or repair is worthwhile. I can't have a new sail built here, only repair the old.

I knew the Aegean was windy before I went there, but nowhere in my guidebooks did I read of 60 mile per hour winds. Or that, when gale force winds are predicted, harbor officials are known to physically prevent charter boat clients from leaving, lest they lose more than a sail. I, as a foreign yacht, was free to do as I pleased, and I did, and now my sail lies broken.

I think one must approach Malta by sea, as the forces of Suleiman the Magnificent did in May of 1565, to understand its basic character and history. On approaching Grand Harbor at the town of Valletta one is confronted by a series of walls rising from a rocky shore. This enormous fortification is The Castle of St. Elmo, ingeniously designed by the Knights of St. John. Suleiman came here with 40,000 men, laid a siege and several attacks against the castle and, after several months and the loss of 30,000 of his men, gave up and sailed away.

In another battle, one perhaps less romantic from a modern perspective, Italian and German airplanes tried to pound the island to dust in the 1940's. These attacks also failed, and submarines and airplanes from Malta continued to haunt the shipping lanes from Italy to North Africa. One of the more fascinating stories of this battle involve three small cloth-covered biplanes that had been left behind in crates by an aircraft carrier early in the war, assembled by the Maltese, christened Faith, Hope and Charity, and then used to hold off the Italian Air Force.

Here I am describing "important battles" again, as if armed struggle was the essence of history. But I think Malta is an exception, a place whose history is quite literally a series of attempted invasions. But apart from this, Malta grabs you and won't let go. The steep town of Valletta is located on a narrow peninsula — one can look down its streets in three directions and see boats sailing by. One is reminded of San Francisco, except for Valletta's greater sense of history and permanence.

Listen: anybody who visits the Mediterranean and passes up Malta needs reality therapy.

I have been thinking about time lately. If I want, I can think of Valletta as a relatively young town, by comparing it to Jerusalem. As an example, cannons were included in the design of the Castle of St. Elmo. Smooth-bore iron cannons that could fire on ships approaching the harbor — that isn't so different from modern technology, not really. On the other hand, to an American Valletta can seem ancient, because it was built before the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan show. Five hundred years before, but, you know, before.

When I was young I held in contempt all history before the invention of electronics. How did people function without radios? Suppose you had an urgent message, what did you do, send someone running through the night? I would pose this question with the sarcasm I thought appropriate to the idea of someone carrying a message by hand from place to place.

But some things have occurred to me since then. One is the charm of a world in which messages must be crafted with great ingenuity and care, to justify the effort of their delivery. And some of history's messengers literally raced against time and death. Consider the story of Pheidippides, who ran from the Plain of Marathon to Athens, a distance of some 26 miles, to deliver news of the Greek victory over the Persians, then fell dead.

The other is the tyranny of modern communications, in which perfectly awful images are transmitted through space at the speed of light. My favorite example of execrable bad taste was the television coverage of the Challenger disaster, in which the all-seeing cameras panned from the fireball to the faces of the astronauts' relatives, who watched the spacecraft blow up and realized their children were dead.

In my time as an engineer I designed part of the Space Shuttle, and fought a few personal battles to improve the safety of the craft (a story I will tell later), so I was already devastated by news of the explosion. How could the President allow a schoolteacher aboard a dangerous spacecraft? Did he actually believe the NASA rhetoric, that it was a bus that went into space?

But then I watched the TV version of the event and saw the quick cuts between the fireball and the tear-stained faces of the relatives. I remember jumping up in my empty house and shouting at the screen, "Stop this! That schoolteacher is someone's mother! Leave those people alone!"

On the other hand, TV brought Americans the Vietnam war, and made us so sick of ourselves that we stopped it. So television's relentless, prying gaze and instant response can be put to good use.

I envision a committee, in some mature world yet to be, that evaluates new technologies before admitting them into general use. The committee asks two questions. One, what is the best use for the technology? And two, what mean, petty, small uses can this technology be used for? But committees create problems of their own. Maybe a television etiquette will come into being over time, naturally, that will make our TV programming seem as silly as the turn-of-the-century practice of stringing electric light bulbs absolutely everywhere.

Malta has brought something else home to me. Valletta is an absolutely charming town, with magic streets and buildings, the air thick with history. It reminds me, as Jerusalem did, that no amount of personal awareness or wonder can ever be enough. The experience of such a place overflows the capacity of one's senses. It has come to me that to experience this place as it should be I need the capacity for wonder I had when I was 12.

This may seem the beginning of yet another lament about my ridiculous childhood, but bear with me. I just have to accept this as an example of my upside-down life. At a time when I was biologically and intellectually ready for the Mediterranean and its rich history, I was being told to get serious, to suppress my more imaginative impulses. Now that I am 45, a time when most men are becoming fixed in their behavior and views, I need the openness to new experience of the young. So I do my best. My favorite ploy is to try to see a place as if I have no childhood experiences, as if I have just landed from nowhere. For me this is an effective mental tactic, besides being almost literally true.

There is another invasion taking place in Malta, and this time the castle isn't holding back the invaders. Over the tops of the classic stone buildings one sees a forest of television antennas. Sicily is only 60 miles North, and the Maltese have discovered that a tall antenna picks up Italian TV. But the forest of metal poles looks terrible. I asked a local person whether any consideration had been given to tearing them down and installing cable. He told me that a contract had recently been signed to do just that.

But the invader has carried off the young people. I didn't need a government pamphlet, only my walks around town in the evening, to discover the young have emigrated to wherever those slick images come from. Most young people seen here are tourists.

(August 15)

I hadn't intended to visit Italy — one can't visit everywhere, after all, unless one makes a superficial whirlwind tour. But after Malta the wind got mean and I had to stop in Sardinia to refuel. I am glad I stopped, even though only for a day.

Cagliari is a port near the Southern tip of Sardinia, not really a town for tourists, which made it more interesting. Almost no one spoke English. I quickly learned the Italian for Good Day, Good Evening, Thank You, Yes, No, and Help!

After I got a supply of lira and restocked my boat with diesel fuel, I decided I had better make a walking tour of the town, lest I visit Italy and not even see it.

The first thing I noticed about the people was they were almost all good-looking. I searched a sea of faces for one as homely as those of my relatives, but had no luck. I tried not to stare too much, but it was shocking to see so much human beauty so indifferently carried about.

The second thing was the friendly and relaxed atmosphere. People you looked at looked back, sometimes smiled. Of course in Cagliari with my red hair and beard I was as out-of-place as a Martian, apart from being a foot taller than the average, so I should have expected to be looked at as often as I looked.

Being in Italy, I decided I should have a plate of spaghetti. I don't know where I get these silly ideas, these algebraic correspondences of mine, like Italy = spaghetti. After walking around for about two hours, I realized a couple of things. One, spaghetti isn't very special. Italians who go out to eat want something out of the ordinary. So not all restaurants have it, or necessarily want to serve it. And two, it was August, holiday time, and most restaurants were shuttered for the month, the proprietors sunning at the beach.

If you own a restaurant in America, you move heaven and earth to be open during a holiday — you know, when people are out looking for a restaurant. So you take your vacation some other time. In Italy, if you did this you would have the beach to yourself, but you would miss your friends. So I discovered nearly all the restaurants were closed, at the height of the evening, hungry people wandering about.

But I found a restaurant that was open, and had spaghetti. I sat down and waited. Half an hour later I hadn't succeeded in attracting the attention of the waiter, who was in animated conversation with his friends, so I left.

But I didn't mind. I saw the town and its people. I was happy with my walk. So I went back to my boat, had chicken stew from a can and watched Italian TV.

Even Italian TV was a surprise, especially late in the evening. In America, television networks have a department called Standards and Practices, which decides what's acceptable to show all those impressionable youngsters out there — in Italy I think the Mafia rubbed them out. On TV some people were taking off their clothes. Others looked as though they hadn't worn clothes in a long time. They were even touching each other, without any clothes on. They appeared to be enjoying themselves.

Of course I was disgusted, and I fully intended to leap up and switch off the TV. But I realized that, if I was going to write about Italian TV, I would have to observe it for some time, otherwise it would be like criticizing a book without reading it. This sad thought was quickly followed by another — it wouldn't do to watch just one channel, I would have to watch all of them. It was my duty.

I decided I liked the people in Cagliari — they seemed to have mastered the delicate art of living. But my favorite story about the Italians comes from Malta. During the war the Italian Air Force would fly over from Sicily loaded with bombs to drop on Malta. But they knew the Maltese were going to shoot at them, maybe even knock down some of their airplanes. Somebody might get hurt or killed. So they would fly within about three kilometers of the coast, the Maltese defenders would start up the air raid sirens and the guns (which could be heard in Sicily), then the pilots would drop their bombs in the ocean, turn around and go home. They would report to their commanders they had left Grand Harbor a smoking ruin and go home. Not so the Germans, who came to Malta later and lost almost 2000 airplanes and pilots.

I write this as Saddam Hussein is leading a huge army into Kuwait, and American forces are gathering in Saudi Arabia. We need more Italian common sense.

(August 23)

|

Ingenious sundial, Mallorca, Spain

|

There's a big church here on Mallorca, a Spanish island off the mainland coast. A big church? — I might be trying too hard to avoid my tendency toward exaggeration — okay, I will go for balance. Let's see. I first spotted it 50 kilometers away, in spite of the normal August haze. I think you could stand a 747 jumbo jet on its tail inside.

It has all the classic elements — stained glass, statuary, monster columns. Anyone who visits — a lifelong Marxist, who believes religion to be the opiate of the masses, a revolutionary Muslim who sees Christians as infidels — is going to experience a moment of complete disorientation upon entering this enormous chamber. It seems the designers intended to overcome the defenses of the most skeptical visitor, deliberately, with malice aforethought, leave them standing lost, saying "Oh, My God / Ach, Mein Gott / Dios Mio."

I think a child entering this place would be struck down in an emotional sense, and, depending on your view of the capital-C Church, placed beyond later meaningful reclamation. A skeptical adult, while not necessarily converted instantly into a believer, could not escape the emotional message of the space, that someone sure as hell believed something to put this up.

I accept intellectually that there are some larger cathedrals farther North in Europe, but my imagination is short-circuited at the moment, so I won't consider visiting them. Or until I have a chiropractor fix my neck.

(September 5)

Before I came to Spain I thought I knew a little about bullfighting. I read something by Hemingway once, but it seems I forgot some important details.

I had this idea that the bull came out from his dressing room and chased a bullfighter around for a while, then after getting hot and sticky, he would go back in the shade and drink some lemonade. Call his stockbroker. You know.

I was wrong. I was never so wrong about anything in my life.

First, the matador always kills the bull. Always. When the bull comes out the little door, he is dead. No going back through the little door, no lemonade. Second, they stick things in the bull of various shapes and sizes until he bleeds to death.

When the bull first comes out, he is extremely dangerous. He has all his blood still inside him, he isn't overheated, he wants to crash into something with his horns. At this stage everybody hides behind wooden barricades. I saw one fresh bull go completely nuts, drive straight into a wall, break his neck, and fall dead. He had been in the ring less than thirty seconds.

Then some toreros and a matador (a torero fights the bull, the matador kills him) come out and challenge the bull to charge them. The toreros are usually understudies of the big star. You know they aren't stars yet because their capes are big. If I go in the ring I'm going to bring my mainsail, that's how confident I am. I'll paint the sail red and wear dirt-colored clothes. And running shoes.

Pretty soon a horseman called a picador comes out and sticks a spear in the bull (the horse is protected by armor, sort of a medieval jousting outfit). When I first saw this I thought the bull should be allowed to chase the toreros around for a while longer before getting poked and starting to bleed. But then I wasn't in the ring.

Then the bullfight begins, the part most Americans would recognize right away from television or those velvet paintings at K-mart. The matador holds his cape out, and the bull, with an I.Q. of 3 1/2, charges through it again and again. Every once in a while another guy races out and pokes these little decorated spears called banderillas into the bull's back. The spear guy has to be fast: he has no cape.

Aren't they being mean to the bull, I thought. There are four banderillas hanging off him, he's bleeding a fantastic amount, he seems dazed. He'll probably fall over any second. As I thought this, the bull jerked his head a little to the right and threw the matador into the air.

The understudies quickly moved in and distracted the bull, and the star got up. Fortunately he was thrown by the bull's head, not his horns. He decided to continue the fight. I'm glad it wasn't me in the ring — I would have wet my pants and been laughed out of Spain. I almost wet my pants anyway.

In the final stage the matador tries to kill the bull with a long, curved sword. The matador waits for the bull to charge and, from a position directly in front, thrusts the sword out and down through the animal's back. Sometimes the matador must charge the bull to accomplish this, in any case it's very difficult and dangerous. Sometimes the bull gets annoyed by the matador's charge and charges at the same instant, sometimes the bull tries to turn away and snags the matador.

But the sword went in and the matador jumped away. Now the toreros gathered around with their capes. The bull made a few more charges, then sank to the ground.

I thought that was all. But after that bull had been dragged away by a team of mules, another matador took a position in the middle of the ring, on his knees, with his cape directly in front of him. I was told later this man was talented but relatively unknown, and wanted to prove himself. A fresh bull loped into the ring, spotted the matador and charged him.

The bull, now racing, seemed determined to squash this kneeling man. At the last moment the matador took the cape in his right hand and swept it across to the left, and the bull leapt toward the moving cape in mid-charge, missing the matador by the width of a coffin lid. Then I did wet my pants.

(September 10)

My first week in Palma de Mallorca I had a new sail built to replace my worn-out jib. But I ended up spending three weeks there, mostly waiting for a piece of exhaust pipe that never arrived (sound familiar?). I couldn't run the engine without it, so I had to wait. And wait and wait. I finally realized it wasn't coming and asked a shop to build one from scratch. It was $260 for what would have cost maybe $30 if the diesel engine dealer actually stocked parts.

A truth about long-distance sailing is that you spend a lot of time waiting for parts, or doing repairs — probably more than sailing. Which brings me to my next anchor story — this one stretches over three days:

I left Mallorca and sailed to Ibiza, another of the Balearic Islands off the Spanish coast. As night fell I anchored in front of some hotels on the East coast. In the middle of the night the wind began to blow very hard from the East, a peculiar wind direction for this season in the Med. So on waking I found myself in the wrong place at the wrong time. I struggled to raise the anchor and sailed for the town of Ibiza, thinking there would be a sheltered bay.

The sail was enjoyable, Ibiza being one of the prettier islands in the Med, and the anchorage at the town looked well-sheltered. But the bottom was all grass, something anchors don't hold onto very well. On the other hand there were about five boats already anchored there so I decided it couldn't be too bad.

I am strict about anchoring. I always test the holding by running the engine at full throttle against the anchor to see if the boat moves. But at this place the holding was so bad I ended up cruising around the other boats, dragging 400 pounds of anchor and chain behind me, hoping to find a spot the anchor liked. I'm sure the other boats had me marked down as a nut-case by the time I found a barely acceptable spot.

I wanted to go ashore and see the town, but the wind kept getting stronger and I didn't dare leave my boat. I decided I would go ashore the next morning, usually the time of least wind. I got my dinghy ready and then read a book.

At dawn a thunderstorm approached and the wind hit 60 knots. Every boat dragged on its anchor — from the smallest charter boat to a big 80 foot motor yacht — all were blown out of the anchorage, fortunately in the direction of a big bay. A schooner didn't have enough motor power to fight the wind and required the help of a tugboat.

I had anchored away from the other boats in the bay, so when I dragged I had time to gather up my anchor without hitting anyone. After the wind died down I decided I would take shelter in the marina. I had just spent 21 frustrating days trying to get my boat out of another marina, but I was very tired — all I could think about was securing my boat and getting some sleep.

I don't know why I thought the holding inside the marina should have been any better than outside. I got into a row of boats, all with anchor out and stern tied to the dock. I performed my usual test and decided the anchor was secure. Then I paddled ashore and set my stern lines.

I was trying to decide whether to have breakfast or take a nap when another thunderstorm approached. The wind came up and my boat dragged again — just like outside. But this time I was tied to the shore, so when my boat was blown against the dock I couldn't just motor away. I called for help at the top of my voice in English and Spanish. Someone came and untied the shore lines and I gathered them out of the water (so as not to snag the propeller) and then started motoring. But someone had left his own personal mooring line floating just beneath the surface (so no one else could find it but him) and my propeller snagged on it. The propeller wound up this line very fast and tried to drag the boat backwards, but instead the drive shaft was ripped off the engine.

So now I had no anchor and no engine, and the wind was blowing me against a concrete dock. Some people came and pushed the boat against the wind, and I put the outboard motor on the dinghy. I took the second anchor into the dinghy and motored out as far as I could and threw it into the water. Then I dragged my boat off the pier by winding up the anchor's line. I didn't expect the light anchor to hold the boat by itself, so I reset the main anchor.

It was then that I found out why all this had happened to me — the main anchor was stuck inside an automobile tire. The anchor had dropped into the tire when I first set it. The anchor's point stuck into the bottom when I tested it with the motor, but when the wind came up, instead of digging deeper the whole thing came loose and dragged. This marina was really a wet junkyard.

So I moved the main anchor farther out — now I had two anchors out at great length, the boat was off the concrete wall, and I could try to fix the engine. First I loosened the coupler, the thing that attaches the drive shaft to the engine. Then I dove in the water and pushed the propeller and drive shaft back into position (thinking of my identical Red Sea experience). Then I tightened the coupler, or what is left of it.

That's as close to the town of Ibiza as I got. The wind kept blowing, I couldn't think about approaching the shore again, so I did what I should have done the day before — I gathered up my anchors and sailed away. The wind was still blowing hard, but I just put out a little of my new jib and had a nice sail out among the big swells. This pleasant sail took away some of the humiliation I experienced at being completely out of control of my boat, tangled in lines, bashing the dock.

My boat has always liked being out on the sea, disliked the land, and hated marinas. There's a saying about houses, something like "we shape our houses, then they shape us." I think this goes for boats too — I am being shaped by her, I am coming to prefer the sea to the land, even when the weather is awful.

Am I beginning to sound like one of those single handers that loses his way on the reality road map and starts talking to his boat? Well, nothing is simple if you examine it closely — I am by nature a scientist, my boat is really only plastic and wood, but — but she is as alive as any person I have known, and more alive than some.

Look at it this way. If you are rewarded for diligence and punished for misbehavior by a piece of plastic, someday it will come to you that the hunk of plastic meets the basic condition we use to distinguish people from things — coherence and consistency. This means two things: we have silly ways to tell people from things, also a good boat can pass a test that some people might fail.

But you want to be a rational person, you want to keep your scientific outlook. So you say "She is just a piece of plastic" and you smile.

I had a pleasant windy sail, but I still needed to sleep. So I sailed around to the West side of the island and found a nice bay, clean sand bottom, sheltered from the wind, good anchoring. No town, no people.

This little bay opens to the South, so I decided to perform one of my favorite experiments — comparing the sextant position with the satellite navigator (satnav). I started this voyage relying on my satnav for positions, but I packed a cheap plastic sextant, just in case, you know. Then in the South Pacific, as Bora Bora disappeared in the East, the satnav died. I was obliged to find my way to Fiji with the plastic sextant.

The results weren't great. One day I was 18 miles from where I thought I was. So when I got to Fiji I bought a better sextant made of metal — and a new satnav.

A sextant is just a fancy gadget to measure angles. If you are on the ocean and have a clock and a sextant, you can figure out where you are. You just measure the angle between the horizon and something in the sky — the sun, a planet, or a star. Then you either measure something else or wait for the first object to move some distance and measure it again. I usually measure the sun in the morning and again in the afternoon.

We live on a ball in space (right here I had intended to write the most lucid paragraph ever written, at the end of which you would know exactly why measuring the sun's angle twice in a day tells you where you are on the earth. The paragraph kept getting longer and longer as I tried not to leave anything important out. After all, not everybody is a rocket scientist. But when I found myself starting with "we live on a ball in space" I knew I was done for).

I wrote a computer program that takes my sextant angles and times and figures out where I am. It's just like the old-fashioned paper-and-pencil method but it's fast. Also the program knows where the sun is, any date and time. This program is so easy to use it makes me picky. I usually take three sights in the morning and three in the afternoon, and average the results.

The books say position accuracies better than ten miles on a small boat are good, because the sextant operator gets bounced around a lot, also he is close to the level of the water, which means waves sometimes get in the way of the distant horizon. By comparison, a big ship gives you a higher viewpoint and rocks a lot less.

So I sometimes find a bay that faces South and anchor there. The water is usually calm and the boat doesn't rock. Under these conditions the only errors are my own — not holding the sextant steady, not reading the angle scale correctly, not being patient.

My test took all day (with digressions for swimming, washing clothes, eating, stuff like that). I turned the satnav on and let it collect positions, which I then averaged (since satnav positions are not perfect either). Instead of using a wristwatch to record the times of my sights, I connected a push-button to my computer and pressed the button to mark the times. That way, when I saw the sextant's image of the sun touch the image of the horizon I could just push the button.

In the past I have tried to look from the sextant eyepiece to the watch really fast — a very tricky business. Either you swing your head without moving the sextant, which may leave you permanently scarred, or you push the sextant out of the way really fast, which means after you write down the time, you have to go diving for the sextant to find out what the angle was.

Well. After taking a lot of sights and computing the results, I found the satnav position agreed with the sextant result to less than 2/10 of a mile (850 feet, to be exact). This is good, if I say so myself. In fact, to do any better I would have to measure time in fractions of seconds, because one second of time changes the result by one-quarter mile.

On long crossings I sometimes take sextant sights just to pass the time, and I have wondered how accurate a sextant is under controlled conditions. Now I know it is as good as a modern electronic wonder like satnav (some old-time sailors say "better").

(September 17)

I visited Granada while traveling the coast of Spain, on the strength of a rumor that they had a nice castle.

The "nice castle" is called the Alhambra, which marks the Western reach of the Moorish empire. It sits on a hill overlooking Granada, the traditional capital of Spain, and the resting place of Ferdinand and Isabella.

I can't compare the Alhambra to anything I've seen before. Over a period of eight centuries monarchs competed to possess, and then to add to, this high fortress. Most of the architecture is Moorish, although some Western influence can be seen in recent additions.

I kept moving from place to place within the outer walls, and seeing more fountains, gardens, and palaces — walls covered with the most beautiful and delicate stucco and tile patterns. After several hours of this, I sat down in a stupor and glanced at my guidebook. The book told me I had spent my time in a part of the fortress devoted to administration in those far-off days — there was another palace, across a ravine, where people went to enjoy themselves.

This is unbelievable, said I. This place is a heaven of rooms and gardens, tended by invisible keepers whose greatest joy in life is to find an untrimmed cypress, an unswept walk, a fallen gum wrapper. How could that green land across the footbridge be more beautiful than this?

But it was.

(October 2)

|

Author with the Barbary Apes in Gibraltar

|

I am in Gibraltar, the place the Greeks called the Pillars of Hercules. To be more precise, I am on Gibraltar, as windy and exciting a piece of rock as I have climbed. I can see North Africa and Spain in one glance, with a strip of water between. Beyond is the Atlantic, the last major ocean I haven't sailed.

When I pass through the Straits of Gibraltar, for me, a modern sailor, it will be just another blue place on my charts, another step toward home. But I want to imagine the thoughts of the great ocean explorers, for whom Gibraltar was the end of the known world.

When I was young I remember a row of trees that marked the end of my world. Those trees were as far as a rusty bicycle would carry me, and the land beyond them stood unexplored as I languished behind panes of glass, pale and mute, waiting for a bell to ring. Any bell.

I knew there was something beyond those trees, apart from a fence and a hill. But I would be thinking about something else. I pedaled up to those trees and turned away so often that they became a pretty solid barrier.

One Saturday a Navy fighter plane blew up over my neighborhood. The plane's entire load of jet fuel, scattered across the sky by an exploding turbine, burned up with a thunderclap, and stopped a conversation I was having about marbles.

A flashing red light warned the pilot that something unpleasant was about to interrupt his flight, and he ejected himself a second before the explosion. My friends and I saw the pilot as a tiny black dot, then the parachute canopy opened above him. We saw the broken airplane, trailing orange flames and black smoke, falling to the ground. To an adult, this would have been a dramatic event, a reason to turn off the television and go outside, but in my glassed-in life it was a wake-up call from God.

The plane crashed on the hill that was just beyond the end of the world. I jumped on my bicycle and rattled and clanked my way to the row of trees, now made small by a pillar of smoke. My friends and I clambered over the fence and moved as close to the wreck as we dared. I tried to pick up a bit of metal, but it was too hot.

I had to remember to breathe. An airplane, one of those dull punctuation marks in the sky, had broken and fallen to the ground, had become orange fire. While falling it had traveled as far as I cared to pedal my little bones, I mean until then. It was a metal death bird, and its rider was lucky to have escaped it.

Then some Navy people appeared and made us leave, without any souvenirs, and I turned back toward my neighborhood, suddenly small behind the trees. The contour of that hill was now part of my map of the known world, along with burning airplanes. In my dreams of the following weeks, more airplanes burned up than could possibly have been supplied under the Navy's budget.

So who am I to laugh at people who turned cold at the thought of passing the Straits of Hercules, or at Columbus' sailors, terrified at the prospect of falling off the edge of the world? Until an airplane fell out of the sky, I pedaled my bicycle up to that row of trees, carrying two peanut butter sandwiches in a brown paper bag, and turned away toward the school, day after day, for years. I displayed the curiosity of a turnip.

(October 12)

I am in the Canary Islands now, making arrangements to fly to Germany to visit Bob and Ursula, my friends from "Take Two" whose voyage has now ended, and who are making an uneasy reentry into normal life after several years of sailing.

It's a good time for a side expedition. The best time to sail from Gibraltar is before the end of September, but one must wait until the end of November to continue across the Atlantic, to avoid the hurricane season. Most people wait in the Canaries.

(November 8)

My friends Bob and Ursula live in Staufen, a small town near the French border in Southern Germany. The Black Forest and the Rhine River are close by, and many of the German wines are produced there. For two weeks I explored the area by bicycle and on foot, mostly in the forest and among the vineyards, but with some visits to towns and households thrown in.

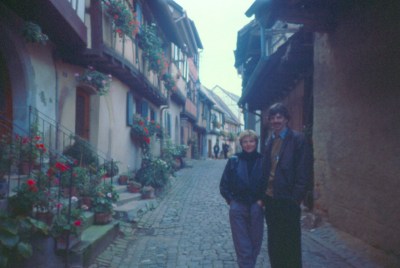

|

My friends in a French town

|

The countryside is a study in beauty and order. When you come to the edge of a town, the last house goes by and you are in the country — no suburban developments, no billboards, just a fence and then open land. And no litter, either, not so much as a bottle cap. When I asked Ursula "how come there's no litter?" She just looked at me and said, "They shoot you."

I knew Ursula well enough to get her meaning. She says that kind of thing for two reasons. First, she knows Americans will do anything that won't get them shot, and second, she likes to make fun of Americans' view of Germans. We've seen too many war movies, too many Nazis from Central Casting. We expect to see Germans in the town bakery shouting military commands at each other.

But Germans are also preoccupied with history. Some would like to get a divorce from their own past. In America when I was young I heard about the "Good German," the obedient citizen who heard of atrocities but paid his taxes and did nothing. Since Vietnam I hear that expression less often.

One day we had lunch at a schoolteacher's house. This man spoke several languages including English, and he kindly tolerated my German. He was also a good cook, and brewed wine from the grapes in his garden.

After lunch and wine the German conversation got too fast for me to follow, so I picked up a photo album. I happened to be turning the pages from left to right, that is, from the present toward the past. Soon the countryside picnic scenes gave way to snapshots of the war. The schoolteacher's father standing next to a crashed airplane. A group of soldiers, posing for the camera as tourists do.

The schoolteacher's daughter pointed out her grandfather in the album, then wandered into the TV room. I must have appeared to be idly leafing through the album, but my mind was racing. Can this man take pride in his father's war service without sanctioning the policies of the era? Who gets responsibility for the crimes of that time? All Germans? The military? People with political power? Obedient followers? The schoolteacher's daughter?

I realized I was posing questions rapidly that Germans probably pose to themselves over a period of years. And, I hope, Americans as well, now that we've experienced Vietnam. From the perspective of the couch I sat on, I decided that trusting a state is dangerous, and outright obedience is disastrous.

I think America's track record is comparatively good for such a large and powerful country, and I think I know the reason. We usually stay out of trouble by electing only morons to public office. If we accidentally elect a non-moron, we usually don't trust him or do what he says. If both these safeguards fail, we can be made to feel great public embarrassment, even shame, to a degree not possible in a mature European country.

Germans are loyal and efficient, and these qualities produced a disaster without parallel in human history. But Germans have long memories — today's students know the names, dates, and events of the Thirties and Forties, and show a healthy degree of skepticism about public affairs.

So I closed the photo album and rejoined Bob and Ursula, and we walked home through a pretty vineyard. As I walked I thought, I'm no more afraid of the Germans than of the Americans. And no less.

November 25 — Day 5, Canary Islands to Caribbean

You can sail your boat in the Canary Islands, but it is tricky. There are few natural anchorages, and none is entirely safe. Most of the nice bays have been taken over by dreadful marinas that offer small shelter from the rough water, and charge you for the privilege of being there.

As I prepared for my visit to Germany I discovered that all the boats in Las Palmas marina would have to leave, to make way for a fleet of boats taking part in a transatlantic race. So I had to find another marina on the island, move the boat, then bus back to Las Palmas to catch my plane.

When my trip was over I found my boat bashed and broken. The only marina with space available offered only slight protection from the swell, and the people there didn't care about the boats as long as they got their money. My stainless steel bow pulpit had been smashing against a staircase, and my rail against a concrete wall, as I sat drinking wine by the Rhine River. I would have been better off leaving my boat in Las Palmas at anchor, outside the marina, an idea that seemed irresponsible until I saw the aftermath.

I was able to bend the pulpit back into shape with block and tackle, but I felt shame anyway, as though I had betrayed my poor little boat. Until I flew to Germany I hadn't left the boat anywhere for longer than a day, afraid that something bad would happen. I found a marina, tied the boat securely, but something bad happened anyway.

When I got back, most of the fleet of transatlantic racers had arrived and filled the Las Palmas marina to overflowing. Many of the racers hadn't crossed an ocean before, and some were at the extreme level of inexperience. Every race year a few boats run out of food or water in the relatively easy Atlantic crossing. Can you imagine planning an ocean crossing and not packing a few extra cans of beans?

I overheard a conversation as I walked alongside the boats — a little girl asked, "Mommy, how do I start the stove?" and her mother, visiting a nearby boat, called out "Just turn the knob and find a match, dear." An ordinary conversation, unless you know something about boats. You see, propane is heavier than air and sinks to the lowest place it can find. In a house it just runs out below the kitchen door and annoys your dog. On a boat, a big plastic teacup, watertight and airtight, the gas collects in the bilge. Eventually there's enough gas down there and the boat blows up.

Elaborate precautions are taken to keep the gas from escaping unburned and collecting in the bilge — electric safety valves, warning alarms — but if you turn the knobs on the stove, the gas comes out, just like at home.

So did I butt in and lecture these hotshot sailors on the dangers of propane? Not on your life. Some likely outcomes flashed before my eyes — The woman emerges and bawls out her husband for enticing his family onto a boat that is dangerous even while tied to the dock. Or, she confronts me and says "My daughter and I have circumnavigated the globe three times, you miserable sexist. We just haven't lit the stove yet." Or the daughter, match in hand, lifts a bilge hatch and says "Gas? I don't see any — "

boom.

By the way, I have a kerosene stove. It smells bad and is hard to use, but my boat won't blow up.

Anyway, their boat didn't blow up, or if it did, I didn't notice with everything else that was going on. Would-be sailors crowded the marina, petitioning boat owners to take them across the big water. They even commandeered dinghies and rowed from boat to boat, pleading to be taken sailing.

There are a number of arrangements between boat owners and crew members. In one, the crew are professional sailors, cooks, etc., and they are paid. This is the usual arrangement on big yachts. In another, people agree to work for free, for the experience of sailing. Finally there are boat owners who make you pay to sail with them. At first I didn't realize people were that desperate to sail, but plenty are, although they are usually the least experienced sailors and many regret the arrangement almost before casting off.

The bulletin board at the marina made interesting reading. Some male boat owners had posted notices asking for females to apply for crew positions. Did I say "Qualified female sailors?" No, and neither did they, just "Females." I thought this rather blatant, but I actually saw one female in the act of applying. She approached a boat and asked "Are you seeking crew?" The owner bounded out of the hatch with somewhat more than the minimum effort required, and spied the applicant, an Englishwoman of about fifty years, conservatively attired in an ankle-length flower-print dress, straw hat, and practical shoes.

She was female, the only listed requirement, and she bore herself with quiet dignity. For all I know she was supremely qualified, had done postgraduate work in navigation theory and been a sailor from a tender age, but I also know what this skipper wanted to see, and she wasn't it.

The skipper lived a frozen moment with his mouth hanging open, a fish caught in his own market, as he realized he wouldn't be able to explain his requirements to this serious, dignified woman. If truth in advertising were required on bulletin boards, his notice would have said "Nut-brown, smoothly muscled young females desired for Atlantic crossing. Applicants should be stupid or brain-damaged, coöperative, and physically appealing. Previous experience not necessary or desirable."

But I don't know what happened next, I was just walking by. And I set sail the next morning for the Caribbean, sort of on a whim. It turned out my timing was good, I had decent wind for the first few days. Many of the Atlantic race boats are in that area now and they have either no wind or contrary wind. They were part of an organized event and so they had to leave on a predetermined day — no whims allowed.

I remember how anxious I used to be at the start of a long crossing. Now I find myself relieved to be underway. I can organize my thoughts, review where I've been and where I am going. Write in my journal. Make plans. And watch the sea go by.

This morning, probably because of the smooth seas, I was thinking, what's the biggest wave I ever saw? How did I figure out what to do with it?

I think you learn the basic lesson of the sea by watching a wave bash a sea-wall. After that you know what must be done. You give the sea what it wants. You mustn't give too much or too little, and it must be on time. You either wake up and change the sails or the sea rips them for you. There's no hearing, no appeal, no excuse.

And no jury. If the sea takes you, you can't blame a corrupt system of justice. Maybe you bought the wrong boat. Or you sailed when storms are likely. Or, worst of all, you were disrespectful. I think you can learn to have a flawless lunch with Queen Elizabeth more quickly than pass muster with the sea. Meaning no disrespect to the Queen.

December 14 — Day 24

It's been a beautiful sea. When the wind stopped for a few days, I just drifted around. The noise of the engine would have spoiled the perfect blue silence. I went swimming and checked out my boat. Then I looked down, following the boat's shadow into the deep. The water is very clean and very blue.

The next day one of the Atlantic race boats came by. I saw him coming and prepared a gift — I tied a float to the end of a long line, and tied a bottle of wine onto the float. The I let it float aft. That way they could collect the gift without having to come too close. They caught on fast — by the time they had hoisted my bottle they had one ready to give me. I was a little embarrassed — I sent over a bottle of ordinary Spanish white wine and got back a bottle of champagne.

I've been hearing the race boats on the radio — some of these boats are way too much for their owners. One guy has hydraulic steering and can't make it work — so he can't steer his boat. He's been having long radio chats with people who know about hydraulic steering.

Another boat started taking on water. I don't know the whole story yet, but the crew just got onto another boat and watched theirs sink.

I'll give them the benefit of the doubt and assume they had a leaking rudder post. That's one of the nastiest problems you can have. On modern boats, a rudder post sticks through the bottom of the hull and connects the rudder to the steering gear, usually a wheel in the cockpit. But if the rudder hits something, the watertight seal can break and water starts coming in. Sometimes the seal breaks without waiting for a special reason.

There are some remedies. The most effective is not to have a rudder post. On my boat there's a big stick called the tiller, which runs off the back of the boat and attaches to the top of the rudder — so I don't need a rudder post. It's an old-fashioned, even ancient arrangement. Nobody thinks I have a race boat, but I have one less hole for water to come in.

Another trick is to have a tube inside the hull, surrounding the rudder post and rising with it above the waterline. So if the rudder seal fails, the water can only fill the tube, not the boat.