Chapter 3 — Hawaii to Marquesas

I am starting this journal chapter while tied up in Hilo, before departing for the Marquesas, so at least the beginning will be coherent. When I am underway no night's sleep is completely uninterrupted, so that the perfect word or phrase is taken from me by force, as I wrestle with a sail that is a lot more awake than I am.

I spent last summer sailing from one gorgeous island to another, starting with the Big Island and making my way to Kauai, which turned out to be my favorite. I began to dive each day, exploring the island reefs. At first I thought I would use my SCUBA tanks, but refilling them was too much trouble, so I began to free-dive (with fins and mask but no tanks). Free-diving turned out to be a good idea — I dove a lot more by not needing a tank for every dive.

The reefs in Hawaii are beautiful, and the fish are interesting. I saw several octopi — they are supposed to be intelligent and they are certainly shy. Also some white-tipped reef sharks — not particularly dangerous unless cornered. I started staying down longer and longer on a breath — by the end of summer I could stay down three minutes.

Also I bought a wind surfing board, one designed for Hawaiian wind conditions — when the wind stops, the board sinks. I found some excellent wind surfing beaches, both on Maui and Kauai, where the wind blows steadily all day, and if you are good you can lift off the bigger waves and fly through the air.

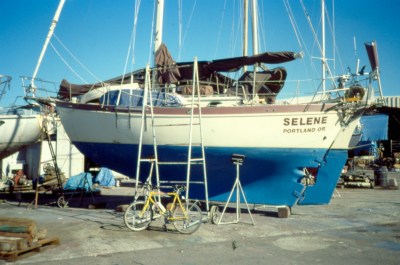

In the fall I sailed my boat to a marina in Honolulu for winter storage and flew back to Oregon.

I returned about February 10. I had intended to stay in Oregon somewhat longer, but I wanted to paint the hull of my boat and the Honolulu boat yard I wanted to use would be closing for two weeks at just the perfect time.

When I arrived at the marina, everything that could have been wrong with my boat, short of sinking, was. The cockpit was full of water, the water level in the bilge nearly covered the cabin sole, and the batteries were flat. At first I couldn't get into the boat because the padlock had rusted shut from non-use. All this for $250 a month, frequent phone calls, and reassurances that they were looking after my boat. You can't imagine the indifference to boats and boaters in Hawaii — you have to see it firsthand.

I had left the flexible solar panel connected, thinking it would keep up with the bilge pump and charge the battery. Then while I was in Oregon I imagined the sun beating down, keeping the batteries happy. But no — once the bilge pump started, the solar panel lost the struggle for the batteries.

I took my boat to the yard and they hauled me out. I replaced some of the valves that pass through the hull, that seal my boat from the outside world. One of the original valves simply wouldn't close any more. The handle had fallen off another. I might use these valves to save the boat if a hose burst, so they have to work. And one can only replace them when the boat is out of the water.

I also cleaned and painted the boat's bottom, something I hadn't done before. I have a feeling I will be doing that regularly. This boat sails noticeably better with a clean hull.

I had a great sail recently. I wanted to sail from the Southwest corner of Molokai to Lahaina on the West side of Maui. It was blowing hard (30 knots) and I needed to go upwind, so I wasn't expecting smooth sailing. But, since I had just painted the boat's bottom and was willing to trim sail a lot, I had a chance.

If you've been paying attention until now, you know you can't sail directly into the wind. When you want to go in the direction the wind is coming from, you have to sail off the wind about 45 degrees one side or the other, and switch sides occasionally. When you switch it's called "tacking." So I started out by sailing across the channel between Molokai and Lanai, then tacked back. This moved me several miles. I quickly realized it was going to be one of those days when the boat would sail itself — I just tied the tiller with a line and the boat sailed itself at just the right wind angle. Then I spent some time trimming sail for best efficiency.

When I got to Molokai again, I thought I might just make it past the East side of Lanai on the next tack, which would get me on my way to Maui. So I just tied the tiller again and let the boat sail itself. I spent my time whale watching.

|

Anchored at Tunnels Reef, Kauai, Hawaii

|

You may not believe this, but during the next six hours the boat sailed itself across to Lanai, past a place reassuringly named Shipwreck Point (with a rusted freighter aground, lest anyone miss the point), and across the channel to Maui. At about sunset my boat had followed the wind to within one mile of my destination — and I hadn't touched the tiller all day. It was a great sail, not to mention that I saw several whales doing various whale-type things.

I am collecting more anchor stories, without honestly wanting to. In the 90 days since leaving the boatyard I've collected three. The first took place in Haleolono, on the South side of Molokai. Haleolono is one of my favorite anchorages. It's small but well protected, there is no town nearby, and there are some nice beach and backwoods walks. When I arrived I was alone in the bay, so I took the center and put out plenty of anchor chain.

But a three-day weekend was coming up and boats from Honolulu started appearing. Soon they packed the bay. On Saturday afternoon one of the last arrivals was a 20-foot sloop with three people on board.

I had a funny feeling about this particular boat, so I watched it. Then I noticed the Coast Guard Auxiliary flag on its mast. That's it, I thought, this guy will turn out to be the least competent sailor in the bay. This cynical observation came to me because of my experiences with the Civil Air Patrol in my time as a pilot. Supposedly paragons of virtue around airports, in my experience they tend to be the worst pilots, getting themselves killed in greater numbers than their vanilla counterparts and generally making life miserable for everybody, while occasionally going out to search for a downed plane. But I digress.

This guy motored around my boat a couple of times, even though there was no room to anchor near me. On the third time around I watched him, anchor in hand, pass across my anchor rode looking to windward. Without looking aft, he dropped the hook — right on top of my rode, and about 50 feet in front of me. Things deteriorated quickly after that. Within three minutes he had wrapped his line around my chain, around my boat, around his keel, and around his propeller. I watched it, I have thought it over since, and I still struggle to believe it, but there it is.

Now that he had no anchor and no motor, he began to drift toward my boat helplessly, and I pushed him off so we didn't crash. When he drifted aft and the amazing tangle of line grew taut, he began to realize his predicament. I saw it was time to put down the binoculars and do something.

First I rowed over in my dinghy, thinking I would raise his line and untangle it. At that point I didn't realize how bad things were. Failing at this, I put on my free-diving outfit and dove on his boat. The boat's skipper floated alongside wearing a snorkel and mask, and he poked with a boathook at eight turns of line around his prop. But he wouldn't go below the surface of the water! Meanwhile another crew member tugged and pulled on the line, apparently thinking about the rocky breakwater 200 feet aft, thus making it impossible to untangle it.

So I made a couple of suggestions to the crew, then unraveled the line in repeated dives on his boat, my boat, and my anchor. I thought to myself, this guy is way behind the situation — he hasn't acquired the water skills he needs to rescue himself from his own lack of anchoring skill. His boat's continued existence depends on the good will of those around him. I had seen examples of such utter dependency in automobile drivers before, but this was my first example on the water.

The setting for the second anchor story is a bay on Maui called Honolua, a pretty marine preserve on the Northwest part of the island. It's a small bay that can safely hold about three boats. I wanted to spend some time there, write letters and dive on the coral reefs, and when I arrived I found it empty. Perfect, I thought, no interruptions, nice solitary dives.

After I had been there a day, a big kona (South) wind started blowing, and I realized I was in a rather good place to ride out a storm, so I put out another anchor and decided to stay longer. I heard radio reports of awful wind and wave conditions at Lahaina, where I normally anchor.

On the second day of the storm I was napping in the afternoon when I heard someone trying to hail me. I came out on deck to see a boat directly astern, banging on the reef. The boat had no anchor and no motor.

Without thinking about what I was getting myself into, I tossed him a line and began to haul him off the reef. I had securely anchored my boat, using a full-chain rode to a 35 pound CQR (a kind of anchor — pronounced "secure") and a chain-and-rope rode to a 25 pound CQR, both buried in sand. I had gone down and inspected both anchors so I knew they were firmly set. Because the wind was gusting to 25 knots, I used a sheet winch to haul him off the reef. The skipper implored me to pull him off faster. I struggled to move him. Finally he reported he couldn't hear his boat smacking the reef any more. As he said this, his boat surged forward and crashed into my aft pulpit, mangling my windmill mount and satnav antenna.

Now I had hauled him off the reef and his boat had crashed into mine. If I drew him any more forward his bow would get intimate with my engine compartment. If I slacked off he would go back on the reef. On top of everything else the wind was getting stronger. So in a moment of acute insensibility I loaded my third anchor into my dinghy, motored over and attached it to his boat, then stretched it out over the bay. Once the hook was in place the skipper started hauling it in, bringing his boat near mine and smashing me a couple more times.

Once he was clear of my boat so no more collisions were likely, I suggested we take a break and plan our next move. It turns out he had an anchor but he managed to drop it over the side without first attaching it to his boat. So we dove for the anchor and made up a rode for it out of scraps of line he had on hand. But he didn't like that anchor. He wanted to keep mine for a while.

For the next three days I towed his boat around the bay with my dinghy and outboard, setting and moving various anchors, took him ashore through the breaking surf and back to his boat (his dinghy sank during his last sail), all in trying to get my anchor back so I could leave. When I finally got back to Lahaina it turned out he has collided with every boat he managed to approach, and his boat is a gallery of scars from previous collisions. The skipper is well-known, not to say notorious. Repairs to my boat take about a week.

The third anchor story is all mine. One day I stopped at Molokini Crater, a crescent-shaped bay on the way from Maui to the big island. It's one of my favorite stopping places and it breaks up an otherwise long passage. This particular afternoon the wind was strong and the waves were somewhat bigger than usual, and the crater was a lee shore (meaning the wind would blow you toward it). After I arrived and set my hook, I decided I was too close to the reef. So I started my usual single-handed procedure for changing position: go aft, start the engine, go forward, raise the anchor, go aft, motor to new position, go forward, drop the anchor, and so forth.

So I raised the anchor, secured it, and ran aft to motor away. I couldn't waste any time — as soon as the anchor came off the bottom, the wind started moving the boat toward the reef. I jumped into the cockpit, hit the throttle and grabbed the tiller in one motion. Then I glanced aft and realized the dinghy wasn't trailing behind as usual: after I raised the anchor the boat and the dinghy drifted together. So naturally the dinghy line got sucked into the prop. The line tightened and the motor stalled. Now I have no motor. So I sprint forward and drop the anchor again. Don't forget the boat is being blown ashore all this time — by the time the anchor takes hold, the hull is nearly touching the reef.

So now I have an emergency on my hands. The bottom of the boat is inches from the reef, the wind is trying to blow the boat onto shore, and the waves are breaking all around. I grab a diving mask and jump over the side, and for the next five minutes I use my pocket knife to cut the dinghy line away from the prop. On the third of these dives I stay down a long time, tugging and cutting the line and watching the hull come nearer and nearer the coral, so when I am ready to surface I am desperate for a breath of air. I reach over my head to bring myself up and manage to stab the dinghy with the knife, deflating one of its sections. But I have the welfare of a bigger boat to worry about. I pull my wet self aboard and start motoring against heavy seas and wind, dragging the anchor across the bottom. It takes about 20 minutes to move 500 feet.

The boat smacked the reef once during this episode, making a scar in the rudder, and I had to patch the dinghy, but there was no serious harm. I spent a few days wondering whether I had fallen out of grace with the sea. I finally decided if I had, my boat would have shifted and squashed me against the reef, and the sea was merely reminding me of the small margin between a normal anchoring experience and disaster.

Notice how sympathetically I treat myself in this story of stupidity. I don't get to describe some stranger as a loser in the great genetic sweepstakes as I dive on his boat — it's my boat, it's my dumb predicament. But I handled the situation — no one could have helped me, no one was there.

Today is March 22. I plan to depart tomorrow for the Marquesas. Local sailors say it's not easy to get there from here. One must sail as close to the wind as possible for a long time. Maybe I'll get lucky and a storm will come through, giving a wind direction other than from the East. Otherwise I might have to accept the will of the sea and change course for Tahiti.

I have plenty of new books and I've provisioned the boat well (i.e., many kinds of cookies). My attitude toward this departure is different from my last. I was frankly petrified to go out from the mainland last May. I had so many rough-weather days during my winter practice sails off the Oregon coast that I was able to imagine a month of that kind of sailing. But my fears turned out to be exaggerated then, and the month of April is supposed to be mellow between here and points South.

I still have to go through the adjustment to solo sailing, after a week of frequent visits with other sailors here in Radio Bay. A woman traveling on another boat has raised my morale a bit — we visit and take walks (her boyfriend won't take time away from lacquering the wood on his showplace boat). Her acceptance makes me think I might only have to sail solo on the water.

March 25 — Day 3

On Day 1 I made one last trip to the post office, but a letter from Mary still hadn't arrived. It was a collection of things — a letter from a relative being remailed, some news stories, some bank forms. Now they'll have to mail it to the Marquesas or Tahiti, assuming it isn't lost altogether. Six days seems a reasonable amount of time to move a first-class letter from Oregon to Hawaii.

I raised anchor about 9:30 AM and crossed the Hilo breakwater at 10:15. Winds were very light near the island. Since I want to conserve fuel I motored only until there was enough wind to start moving on sail power.

The first two days were difficult — getting accustomed to being underway and a rough beat to weather. Most squalls seem to wait until the predawn hours, then spring up and oblige me to strike the windmill and reduce sail.

At night I've been running the radar, which is quite a power user, and using the windmill to power it. But the windmill is very noisy and becoming more so, as its mounting wears out under the stress of the boat motion mixed with its own gyroscopic forces. I am tempted to do without the radar in order to shut down the windmill. And I haven't seen any other vessels out here.

My original destination is looking more unlikely. The wind is East Southeast, which has me on a course of about 150 degrees true, too far to the Southeast to make the Marquesas. But I am going to sail as close to the wind as I can for a while longer in case the wind changes direction. I figure if I get due North of Tahiti without any change in the wind I will take that as a sign, bear off a little and pick up speed for Tahiti.

I am impressed by the boat's performance this close to the wind. When the seas aren't too rough, the boat moves at 4.5 knots while 50 degrees off the wind. Of course, that's after three days of sail adjustment.

I am using the wind vane to steer, so in principle the boat doesn't require any electrical power to carry on. I just wish the heavy seas didn't head me off so much — when the surface is smooth the headings tend to be more consistent and more Easterly as well.

March 26 — Day 4

There are plenty of squalls at night and in the early hours of daylight. They mess up the wind direction, so I have to work to keep moving the right way. Today — in the last 4 hours — I've seen 35 knots and 3 knots. But right now it's blowing about 15 - 20 knots and I've tuned the boat for that. I am doing about 5 knots while beating just 50 degrees off the wind. That's remarkable for this boat. The surface is somewhat smoother than it's been, that helps.

I also stopped using the wind vane — it wasn't very efficient, and the boat seemed to wander unnecessarily. I now am "automatically" guiding the boat with a piece of line tied around the tiller. I've learned that a well-balanced sailboat boat guides itself on a close reach, turning as the wind turns. All I have to do is adjust the course from time to time.

I now know about the wind vane that it doesn't work upwind and it doesn't work downwind unless the wind is very strong. I noticed I gained another half knot when I removed it, because of the energy taken by its searching motions and the extra paddle in the water. Maybe it will work abeam. I haven't sailed abeam enough to test it.

There's still no wind change that would favor the Marquesas. But the sailing has been getting better, so I am content to just beat as far East as I can, then when I get to the equator I'll decide whether to continue.

I made a sunshade for the cockpit out of a little tarp. It is a relief to sit beneath it when the sun is high.

The boat collects a lot of water during rough weather and seas. I discovered the beam scuppers are leaking. I must remember to take them apart and seal them when conditions allow. One of these leaks carries water right into a little electronic storage cabinet — everything I put there has to be in a plastic bag.

March 27 — Day 5

Yesterday afternoon and today I've devoted my time mostly to technical problems. I couldn't get the ham radio to tune its antenna consistently, so I began tracing the problem. I thought it would turn out to be an intermittent connection, but I finally realized it was a bad piece of coaxial cable. Of all things, a piece of wire doing different things at different times.

Cruising feels normal again. I can write on this computer without having to grip it with one hand and type with the other. When I am underway I begin to dwell in a fantasy in which I meet life's grand purpose by simply moving the boat through the water. Not too fast or too slow, and with small worry about getting any particular place. So I guess the secret role of the boat's electronic gear and its problems is to keep me from lapsing into a terrifyingly natural state.

The squalls have abated for now. The wind is from 80 degrees at about 17 knots. It seems to be moving from East to Northeast, slowly. That would be a favorable change — it would get me some of the Easting I've been trying for. But I can't go fast today because the water is rough.

Each evening I use the Big Dipper to locate Polaris, the North Pole star, to see how close to the horizon it has gotten. I expect I'll stop seeing it well before I get to the equator, lost in the clouds near the horizon.

The piece of line I have tied around the tiller is doing a perfectly good job "steering" the boat. I just set it for the wind angle I want and the boat follows the wind around at the chosen angle. If the wind swings South, I want to keep sailing while I hope for a change, and if it swings North, I want to follow that change too, and go as far East as I can. So the boat can follow the wind better than I can tell it to, and the boat guides itself better than any of my electronic tillers.

March 28 — Day 6

When I woke up this morning I noticed the radar had quit working. I saw this happen in Hawaii last summer, so I bought a replacement magnetron tube for it. The repair center suggested that as the most likely problem. I stowed the old magnetron after marking it as flaky.

The radar has been working perfectly for five days, all night long, every night. I thought I had fixed it for good.

This failure has some implications. I have been sleeping soundly, thinking the radar's alarm would alert me to an approaching vessel. I certainly can't fix it out here. So I have to accept a greater level of risk. Naturally I accept risk in sailing alone, but I don't want to increase the risk level. For this part of the journey the risk posed by sleeping is small — there just aren't any boats out here. But I will eventually have to replace the radar — since it takes five days to reveal its flaw, it would be cheaper to start over than to attempt a repair.

Rising temperatures seem to be making the radar worse — it has been getting significantly hotter over the past few days. Fortunately there have been fewer clouds as well. In the Inter tropical Convergence Zone near the equator the winds are light to nonexistent, there's plenty of moisture in the air, and it's really hot. So I'll have to be on the lookout for thunderstorms when I get down that way.

I decided to find the old magnetron and erase the nasty things I wrote on it when I thought it caused the radar problem. When I finally located it, I realized why my hand bearing compass, mounted on the midships bulkhead, had been giving bad readings. The magnetron was in a cabinet about two feet away — close enough for its powerful magnet to influence the compass. At night I look at the hand bearing compass to verify my heading without going on deck, and it had been obviously wrong for some time. I had completely forgotten about the magnetron stored nearby.

I am feeling somewhat more resilient about equipment failures. Before I start a voyage I am a total perfectionist — I have to finish all my shopping and repair lists before I'm happy. But as I get underway the true nature of sailing makes itself known to me — only through a shameful design oversight is anything still in one piece at the end of a voyage.

Before I start a passage, I think I can perfect the boat by simply locating some special piece of stainless hardware. Toward the end I am happy if I haven't fallen off and become shark food. But it's not an unpleasant change — after a week I begin to accept the torn and broken reality of sailing.

The trend toward Northeast wind is continuing, and the sea state is improving, although not as quickly as the wind. I am averaging about 4 1/2 knots, and my heading is gradually swinging to the East. If things continued to improve I might make the Marquesas after all.

I contacted Nancy Griffith and her shore station in Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island last night. Nancy is captain of "Edna," a big boat she uses for her island trading business. She had been underway when I visited there last month so I missed her. We talked mostly about computers — Nancy has been thinking about getting one to keep track of things in her cargo business. It was nice to hear her voice. I think I'll tune in again.

The ham rig is now back to normal. I was able to send a message home yesterday, saying among other droll things that no one should panic if they don't hear my messages — any number of things, now known to include bad wire, could stop the ham radio sea link in its tracks.

I have been using the radio more, listening to the B.B.C., thinking about making some amateur radio contacts. Also I have been watching movies. Last night I watched "The Wild One" with Marlon Brando. As I watched, I thought how terrifying a schoolyard killer or an airliner blown to bits over Scotland would have seemed to those who saw this film in the early '50's.

During my last long sail, a service called AFRTS (Armed Forces Radio and Television Service) was broadcasting domestic U.S. news feeds and other typical AM-radio fare on the short-wave bands. I would use it to keep up with American domestic news. But they have come up with some other way to transmit to overseas military bases, possibly using satellites. I'll miss that service. I will probably also discover that the B.B.C. and others provide better coverage of U.S. events.

March 29 — Day 7

The wind has backed around to 40 degrees and 17-20 knots, which is taking me more East than I expected a few days ago. I am now making calculations to see whether I can intercept the classical sailing course for the Marquesas. I am due North of Tahiti today. If I had given up hope on making the Marquesas I could bear off for Tahiti now, but I am going to try for my original destination. This plan requires that the wind not become Easterly again.

I found some rather big flying fish on deck this morning. I suppose I could try fishing, but if I caught something I would be honor-bound to eat it. Also I haven't worked out where on the boat I would clean it. Some sailors I met in Hilo said they just use a light nylon parachute cord with the tackle attached, instead of a rod and reel. That increased my enthusiasm for trying it, since I wouldn't have to dismantle the boat to gain access to the fishing rod. The lures and hooks happen to be within easy reach.

The radar gave a full night of service. I have a new theory about the radar failure that doesn't fault the radar itself — during the night the battery voltage falls too low, the radar gets into a peculiar state that shuts off the transmitter, the battery then recovers somewhat. Then I wake up to find the radar flaky, and an apparently good battery. This theory will be shot down if I let the windmill run all night and get a failure anyway.

I have a roller furler on this boat — this means I can roll up the jib without having to go out on deck to unhank the sail. Also I can change the jib's effective size. There are some ways to make a jib that rolls up without wrinkling, none of which apply to mine. I think most sailors would agree the convenience of changing the size of the jib just by pulling a line outweighs the problems caused by the wrinkles. I may modify this sail when I get to a sail shop — because the jib wrinkles it makes noise and luffs sooner than if it was smooth. With a smooth jib I would sail more efficiently and point closer to the wind.

I am running a single-reefed main, full staysail, and the jib. The jib makes the biggest difference to boat speed and performance because it gets the wind at a somewhat higher velocity than the other sails, and wire-mounted foresails are just more efficient than the others. People have been known to use only a foresail with good results, but in these rough conditions I think the boat balances better with the full set. Also when the wind increases I can strike the jib and run on just the staysail and main for a while.

Today I am at 12 degrees North, 149 degrees West. Ideally, if the winds had favored me up to now, I would be about 200 miles East of here, on the normal route to the Marquesas. The current can't be very strong here — the satnav positions give a true speed that differs only slightly from the average knot meter reading.

It just occurred to me that this passage would be unbearable in anything but a full-keel, heavy boat like this one. It's bad enough listening to the bashing the bow is taking, and having one rail in the water about a quarter of the time. I can hardly imagine what it would feel like in a fast, lightweight boat with a fin keel. No wonder cruising writers discourage use of this route, those that bother to mention it at all.

I haven't seen a bad squall for a few days now. As I mentioned earlier, there is an outward-moving radial wind pattern around all but the smallest clouds, even those with no rain, so if the cloud is to windward the wind picks up, if to leeward the wind slacks off. In an area with many squalls it can be tricky deciding which course to take, to avoid too much or too little wind, to use the wind pattern to advantage.

March 30 — Day 8

The winds are still from about 40 degrees, so I am going as far East as I can. I have decided that maintaining a speed of four knots isn't absolutely necessary for the time being, since I can go farther East if I allow the speed to drop. My overnight average was 3.7 knots, not bad considering I was only about 45 degrees off the wind.

I have set up a waypoint for myself at 6 degrees North, 140 degrees West. One writer suggests that the equatorial counter current (a band of ocean current that runs to the East instead of West) be used to get to 140 West before going South toward the Marquesas. I noticed that the Southern edge of the counter current is at about 6 degrees North — I figure if I make the waypoint I will make the Marquesas for sure. And, assuming the wind continues to coöperate, I'll make my waypoint in about 6 days.

The vane fell off the windmill last night. The windmill has been giving signs of wanting to fly apart nearly since I installed it. It vibrates a lot while running, and most of the shaking ends up wearing out the mount and attachments like the vane. My quick fix was to attach a line to the handle (which hasn't yet fallen off) and tie the line so the windmill faces the wind. Since the boat itself is weathervaning into the wind, this works as well as the windmill's own vane. Better, actually, if you count how much less noise the thing makes when I lash it down — now it can't rotate every time the boat rolls and shake the entire vessel with wasted gyroscopic energy.

I depend on the windmill to keep the batteries up to snuff during the night while the radar and masthead light are on. Again, the radar worked okay and the windmill was on all night. But it hasn't been particularly hot either. I'd like to know why the radar flakes out.

Somebody needs to design a real sailboat windmill. This one is an example of that time-honored American practice of selling a product that no one has tested in real conditions, and letting the customers discover what to change.

I had to take down my sunshade. The wind began tearing it apart, and it was a lot of trouble to get past, for example to go forward I nearly had to crawl on hands and knees. I think I'll have a piece of canvas made to size that can be removed easily.

It's not nearly as hot as it was a few days ago. There are some high clouds, the wind is about 17-20 knots again, nice conditions.

I am trying to identify a new bird, which might be a Laysan Albatross or a Red-Footed Booby. I have to watch for it with the binoculars some more, give it a good long look and compare it with the pictures in my bird book. I have also seen more Red-Billed Tropicbirds, a very pretty, mostly white bird.

I am a creature of habit. When I was in Hawaii I wanted that to go on forever, sailing from island to island, making friends, diving on beautiful reefs. Starting this sail was difficult, although not as difficult as leaving the mainland. I was miserable for about 48 hours, felt close to seasick each evening as darkness fell. I guess I will call it the usual transition malaise. Now I like being out here. Even though it's an upwind beat, I will probably not want it to end. I will read some books, make ham radio contacts, watch birds for days, maybe even put a fishing line in the water.

March 31 — Day 9

I bathed in salt water yesterday, using one of those plastic bags that lets the sun heat the water, with a shower spigot attached. I used salt water soap and even washed my hair — the whole thing worked. It felt great. I read that salt water was suitable for anything except your hair, but the special soap worked even for that. I used the cockpit as a bathtub (it sort of looks like a tub anyway) and hung the water bag on a line overhead.

The wind continues to back around, now coming from 25 degrees. This means the boat's heading is almost East, although because of leeway (the boat's sideways drift) the actual course is still somewhat Southeast. I'm doing all I can to take advantage of this wind while it lasts, pointing as close to the wind as I can, trading speed for direction of travel.

I am seeing more kinds of birds. Sometimes they hover over the boat, as if they are trying to guess what it is. But after watching them for a while, I realized they are also taking a ride on the air near the sails, like the dolphins that sometimes ride along on the bow. The dolphins take advantage of the mass of water pushed in front of the boat to increase their own speed, the birds glide on the air wave pushed up by the sails. Sometimes they seem to be trying to land on the mast, but they always come to their senses at the last moment.

Amateur radio has its moments. Yesterday I talked to someone sitting in a car in Salt Lake City. He was as surprised as I was.

This boat sure takes in water when the topsides get wet. I pump about 5 gallons of water out of the bilge every day, just from leaks through the scupper on the leeward side, the anchor rode lockers forward, the leaky portholes, and the hatch under the dinghy, which gives a squirt every time a wave breaks from windward on the bow.

Someday I am going to own a boat in which the builders have taken modest precautions against the possibility that the ocean might crawl up the sides of the boat from time to time. The only watertight hatch on this boat is the one I installed in Lahaina just a few weeks ago. After a rainstorm I realized nothing I could do to the cabin top hatch would ever stop it from leaking, so I bought a European-designed hatch that has a huge window in it. It's the same size as the original hatch, it just lets in more light and no water.

April 1 — Day 10

What a night! Thunder and lightning, wind varying from none to 30 knots, big waves from every direction, the works. I may get a repeat performance this afternoon and evening, but I hope not. Right now I'm headed East using the auto pilot to steer with winds abeam. I'm making over 5 knots, highest speed in many days. I am using the auto pilot because the wind is varying too much in direction to use my trusty line-on-the-tiller method.

I have started checking in to one of the amateur radio maritime nets. I give my position and some other important facts each day at a prearranged time. I decided since I was talking to hams every day I might as well try this also. It also gives me a chance to hear where other boats are sailing.

It is very wet, and there's no sunlight for the solar panels. I almost broke down this morning and started the engine, during a spell of no wind. I'm glad I didn't — later I noticed every line on deck was trailing out the scuppers. One of them would surely have fouled the prop. So I went forward and cleaned up the mess, coiling and hanging every line.

It's exciting, watching the lightning after dark, counting off the seconds for the thunder, noticing whether any of the flashes is to windward, thinking how much electronic gear would get wiped out in a stroke.

April 3 — Day 12

There are some landmarks on this cruise, most of them just abstract curiosities. I passed the halfway point last night — now Hilo is farther away than Nuku Hiva (both about 1000 miles). There's 140 degrees West longitude, the point at which I officially can make it to the Marquesas, even though I am reasonably sure already — that happens about two days from now.

There are the equatorial counter current's North and South limits — At 8 degrees I think I may already be inside the borders of the current and getting a small additional Eastward push. There's the day when the sun is directly above, after which it will be to the North of the boat — about four days away, at 5 degrees North latitude (early April position). There are the dreaded doldrums, areas of no wind and occasional thunderstorms, where I may have to motor across, a privilege not extended to old-time sailors, who sometimes waited weeks for some wind to come along. There's the equator itself. All these are new experiences for me.

I still haven't decided how far East to go, before curving back West to Nuku Hiva. If the winds near the Marquesas are Southeast, I will be glad I went East a good long way, so as not to be sailing too close to the wind at the end of the crossing. If they are Easterly, that extra distance will be wasted.

I am still sailing with the tiller tied down. I have experimented with the electronic tiller from time to time, but decided I got the best results with the simplest method. If the wind changes direction, I still want to sail, so I might as well follow the wind rather than the compass. So far the desired compass course and the wind course have been very close.

Once I get reasonably past 140 West longitude I will either use the electronic tiller or the wind vane to get a sailing angle more abeam (wind from the side), for the equator crossing. I have been moving East at a relatively high latitude because the winds are strong and more Northerly than they supposedly are at the equator. I need to be sailing closer to a beam reach when I meet lighter winds, just to keep moving.

I finally saved an innocent flying fish. Late last night I was sitting out on deck with the boat lights turned off, looking at the stars, when I heard a fish-like racket in the starboard gunwale. I used the flashlight to find a flying fish that had just jumped on board and couldn't get back in the water. I grabbed his wing and tossed him back. I always wanted to do that.

April 4 — Day 13

Last night was very tough. I must have slept a total of two hours between squalls trying to blow me down, the staysail clew mount giving way, and assorted annoyances. I now have the staysail tied to its boom with a piece of line — inelegant, but I'm sailing.

The radar has been working all night, every night. I've been using what's left of the windmill to keep the batteries charged, and the association between high battery voltage and radar reliability is getting circumstantially reinforced.

Yesterday I put a fishing line in the water. Within an hour a fish had hooked itself, a story that would be more noteworthy if I had succeeded in getting it on board. Since then, no nibbles. The one that got away was just big enough to eat, too.

Today's weather chart shows me in the middle of a band of clouds, some of them squalls. But the charts are nearly 24 hours old when they are transmitted — right now the barometer is creeping up and it's almost clear. I hope I get to sail in the clear for a while, the squalls impede progress by requiring either sail reduction or all-night watches. Also the surface is rough near the squalls.

It's hot and humid. This would be easier to take if I could open ports or hatches, but occasionally the boat collides head-on with a wave, throwing water over the top of the cabin. I am happy to say the new European-style hatch hasn't leaked a drop.

I've decided (again) to sail as close to the wind as possible. If the winds lighten up near the equator I'll have to bear off to keep moving, so there may be no slack in this plan — I'll get to Nuku Hiva only by sailing a close reach all the way.

I want sleep. I want REM sleep. Lack of sleep magnifies the significance of every little crisis, and there are plenty of those.

April 5 — Day 14

Yesterday afternoon I was able to fall off the wind and increase speed because the wind had become even more Northerly than usual, such that for a spell I was actually moving away from the Marquesas. However, during the night a high pressure system moved into position to the Northeast and the wind shifted around to 110 degrees at 15 knots. My course is now South, more or less. I hope this isn't the last of the Northeast wind, or my well-laid plans will be dashed.

A classic of sailing — one day things look rosy, wind favorable, waypoints falling one by one, why not fall off the wind and pick up speed, no need to pinch the wind so hard any more, next day can't move an inch to the East, need to desperately.

I don't have the satnav position yet this morning, but I think I am on three of my landmarks today — the South limit of the equatorial counter current (near 5 degrees North latitude), 140 West longitude (I hope), and the sun directly overhead.

The wind isn't that strong but the swell is now astern, so the boat is moving briskly. Too bad it isn't moving Southeast.

But this course will take me so close to the Marquesas that I'll tack my way in if I have to. It's just a question of elegance, the 2000 mile curved passage that lands me neatly on target, a giant version of my afternoon sail between Molokai and Maui.

April 6 — Day 15

The wind change I saw yesterday may have been an abrupt and permanent shift to the Southern hemisphere's Southeast trade wind pattern. Looking at the log entries and calculating for true wind I see that the wind changed from 50 degrees to 105 degrees magnetic, two nights ago. And it hasn't changed since.

It doesn't say anywhere that the shift from one trade wind to the other has to happen right at the equator. Anyway, notwithstanding the disadvantages of this new wind, the fact that it happened all at once may mean there's no band of doldrums to have to motor through.

And to think I started out looking at the daily weather charts for clues to wind direction. Having spent weeks in winds not marked on the charts, I now realize the chart makers simply draw wind lines around the isobars, clockwise around highs, counterclockwise around lows (in the Northern hemisphere). They have no way to discover what the wind direction is, only what the simplified meteorological model suggests it should be.

They should tell people the charted wind velocities are no more than educated guesses based on pressure differentials and a handful of observations, and the wind directions are fairy tales. Today, for example, the chart calls for an 80 degree wind, when it's 110 degrees — but then it also called for 80 degrees a few days ago, when it was 30 degrees. I guess in an age of diesel-powered boats, the wind direction isn't a weather forecaster's top priority.

But the charts are useful for locating bands of squalls and thunderstorms. That information seems accurate. Of course they just transfer those markings from the satellite cloud-cover image. For this they need no insight into the workings of nature.

Today I am out of the band of clouds on the chart, so I'm hoping for clear weather and no cloud-induced wind changes. The wind usually drops off in the early afternoon (the opposite of the pattern I am used to), then picks up again in the evening and blows steadily all night. If I'm headed for doldrums, the afternoon wind pause will deepen. I've been watching this pattern very carefully.

I haven't been able to contact the radio link to my house for several days now. Conditions on the 20 meter amateur radio band haven't been very good — I hope that's the only problem. I have been checking into the maritime radio network each evening — it's a pleasant ritual. I get to hear where the other boats are (there are 12 in transit, mostly from Mexico), what weather they're having, that sort of thing.

I've been working on my tendency to pick a problem, preferably one about which nothing can be done, and worry about it constantly. The close reach, for example. I keep thinking, I could have let the boat sail Northeast, that last day of Northern-hemisphere trades when the wind actually blew from the North for a while. I could figure out a different sail plan and pinch up higher than I am. That sort of thing. It's the tinkerer in me — I can't seem to leave things alone.

In computer software development, tinkering is the essence of the experience, although it explains why nothing ever gets done on time. I like having my own personal software development projects with no customers and no deadlines. Then I'll tinker to a kind of saturation point, when it occurs to me that even I won't be able to detect any improvement from the tinkering.

So I am trying to curb the tendency (even though, if you think about it, that's tinkering too) by giving myself permission to enjoy the ride nature's giving me, indulge myself in a book, talk on the radio a lot when the solar panels are making extra power, generally enjoy the place I am in.

After that one fish bit my hook during the first hour it was in the water, no more bites. Maybe fish are psychic. Maybe I should change lures — naah. Apart from the fact that's another tinker, I probably wouldn't be in the mood for fish if I caught one.

April 7 — Day 16

Yesterday and today the wind has backed (turned counterclockwise) enough that I don't feel a sense of impending doom, as in being blown completely away from the Marquesas. I am using this new wind direction to make some more Easting, so I have some leeway, this time quite literally. Before it became an English idiom, "having leeway" meant having some maneuvering room on the windward side of a land mass or obstacle, such that you could sail past without going aground.

I did some laundry today — it had started to pile up. I washed the clothes in the sink using Joy and salt water, rinsed once in salt and then in fresh. Now it is all hung to dry on some lines strung about on the stern. I wanted to dry them the best way (wind and sunlight) but I didn't want them sprayed by breaking waves, so my makeshift lines are well aft. The wind is a bit stronger than I wanted, but noon is approaching and the wind has been slacking off in the early afternoon for several days now. Once I've collected my laundry the wind can blow hard again. I don't want to litter the Pacific with my T-shirts.

The wave heights seem to have decreased over the last few days, so I am getting a higher boat speed for a given amount of wind. The sailing has been improving since a few days ago, when I watched enormous thunderheads rising into the late afternoon sky, like huge inflatable buildings in a dream city skyline. I enjoyed the sight, but knew it would be a rough night. It was.

Now I see scattered clouds in the afternoon and plenty of stars at night. I know there's another band of squalls near the Marquesas, so I'm glad for this interlude of calm sailing.

April 8 — Day 17

Today I am within a degree of the equator, and sometime late tonight I cross over into the Southern hemisphere. The wind has been changing direction, but I still am making some Easterly progress every day. I think I can start aiming for the Marquesas at about 7 degrees South, instead of riding close to the wind with the tiller tied down as I have been doing.

The wind blows hardest at dawn, and softest about 3 PM. I have been shaking out a second reef on the mainsail for daytime, and putting it back in for night — ordinarily I can furl and unfurl the jib to control the overall size of the sail plan, but winds that vary between 8 and 25 knots require more than that.

I am thinking about my plan for this year — the Southern hemisphere's cyclone season is ending (apropos, I just heard a report of a storm near Fiji), and it begins again in November. So I have to (1) tour all the islands and tie up in New Zealand in November, to stay and visit through the cyclone season, or (2) move somewhat more quickly and get past Australia before November. There are several alternatives like anchoring in the South Pacific for the next cyclone season, a somewhat more risky plan.

I am also trying to decide whether to travel by way of South Africa or the Mediterranean. One cruising book I have with me makes the Med sound wonderful — I hadn't seriously considered it until I read that chapter. All I have to do I slip through the Red Sea without being kidnapped by terrorists. That sounds easy from the perspective of the Pacific Ocean near the equator, when I haven't seen any vessels since Hilo. I wonder how I'll feel as I pass through the Suez Canal?

|

Dolphins playing on my bow

|

Some dolphins came to play yesterday evening. They swam around the boat and jumped in the air — an unbelievable dolphin show.

I've been looking for the star Polaris in the evening, but there's usually clouds near the horizon. I saw it last at 4 degrees North.

April 9 — Day 18

I'm now in the Southern hemisphere. I am East of 139 degrees West longitude so I've started to use the electronic tiller to set a more direct course for the Marquesas. Now that I'm not pinching the wind so tightly the speed is going up — 5 1/2 knots at the moment. I feel bad about giving up the boat's natural steering, it was very effective over about 1500 miles of ocean.

The weather has been pleasant — the wave heights are decreasing, no squalls in days, mostly sunny weather and consistent winds. My sleep is regular, thoughts clear.

I sat and watched the crescent moon last night and thought about vision. Supposedly our eyes are never better than when we are about ten years old. I read about an experiment conducted by an astronomer who knew this — he compared the ability of young and old people to make out the crescent of the planet Venus, a very difficult object to see with the naked eye. To prepare his subjects he had them look through a telescope at Venus, then look with the naked eye, then report what they saw.

His telescope was made for astronomy, not for baseball games, so there were no extra lenses or prisms to make things appear right side up. As a result the telescope reversed the image of Venus, made it appear upside down. Most of the young observers politely pointed this out, but most of the older observers didn't — they incorrectly believed they saw the same orientation in the sky as the eyepiece.

Because Venus is so difficult to see, the experiment demonstrated that the visual acuity of the young is even greater than had been supposed. It also demonstrated that people don't want to admit that they can't see what they can't see.

When I was ten years old I picked apricots for spending money, then bought a small astronomical telescope. It had a three-inch mirror mounted in a cardboard tube. It was a very modest telescope, but I was a very proud owner.

I spent hours looking at the moon's craters, Saturn's rings, Jupiter, star clusters. That telescope, and my time spent gazing through it, was one of the wedges driven between me and all the things I should have been doing. I was becoming a misfit — I could absorb enough in a day to pass the school's examinations, and was too arrogant and insubordinate to play along with the slow pace of the classroom.

They punished me for things that seem even more ridiculous now. Reading ahead, for example. I was supposed to control my reading pace, apparently to match that of the slowest reader in the class. Notwithstanding the benevolent educational theory behind this practice, I wonder how much benefit that slow reader derived from my whispers and baleful stares.

I also wanted to write before that was on the curriculum. Denied pencil and paper, I scratched words into my desk. That was the first time I was taken to the principal, although he would see me regularly in years to come. I was tugged resisting past a flagpole and manicured lawn into a large building from which I expected never to return.

I whined loudly as I was pulled into position before a big desk and a bigger male stranger (until then I didn't know there were men in schools). This giant male human tried to soften his delivery as he explained that I mustn't scratch marks into my desk, even though generations of misfits had already recorded their frustration there. I sadly missed most of his speech, being in a state of such terror that I wished only to hide somewhere dark. But I did grasp that I mustn't think for myself.

It was with episodes like this that my personal investment in discovery and the public education system were separated forever. My native curiosity was thwarted far too often in those paste-scented chambers, but never more eloquently than by the teacher who said, "Young man, don't be so smart!"

What kind of person would I have become, had mischievous intelligence been cultivated, directed, by an educational system less completely aligned with the interests of the state? It was certainly true that I was of no use whatever to the state (except in the sense that a robbery victim is useful to a robber), but what other discoveries might I have made? What other things uncovered?

After I exhausted the telescope's possibilities, I developed a passion for electronics. At the height of this stage I would collect my neighbors' broken television sets and turn them into powerful amateur radio transmitters. Over time my designs improved until it was possible for the police to summon their patrol cars while I was on the air.

I remember one particular Saturday morning, at a time when my economic and social prospects were as close to zero as the science of numbers allows, sitting in a chilly garage before anyone else had risen, turning knobs on a homemade radio receiver, listening to voices from across the ocean.

At that moment, normal boys my age were gathering in baseball fields, or lost in contemplation of a particular girl, or discussing the insides of automobile engines. I might as well have come from another planet, surrounded by vacuum tubes glowing orange in my dark room. When I finish my transmitter, I thought, my signal will reach across mountains and valleys. People will tune in my dots and dashes. My voice will shake the wheat in Kansas.

I was a weird kid. After I took an I.Q. test in fifth grade, impressions of me among my friends became evenly divided between those who didn't know about the I.Q. test and those who did. For those who didn't I was a stupid nerd, ha ha. For those who did I was an egghead, ha ha.

The annual school spelling bee provided an opportunity for what they now call cognitive dissonance among the former group. Some of my teachers regularly described my dropout status to bring a straying soul into line. These teachers lived in fear that I would again become the school's top speller, an occasion I contemplated with relish.

An educational system like this bears bitter fruit. It taught me that obedience equals stupidity, since I couldn't simultaneously obey and learn anything interesting. And the method is self-defeating for the society that permits it — potentially creative people end up either obedient empty shells or lifelong rebels.

My jib is starting to shred. I should never have used this particular sail on what I knew would be a long upwind haul, it's too light for these strong winds. I will repair it in Papeete — it should hold together until then.

After several days of looking back at the bright red flies at the end of the fishing line and seeing no fish, I decided to haul out the line and look more closely. It turns out the flies and hook shafts were there, but both hooks were broken off at the curve! Some big fish have apparently gotten away. I immediately felt stupid for not having investigated earlier.

ROCKET SCIENTIST TOWS BROKEN HOOK 500 MILES

I was busy reading and eating cookies, he says.

Film at 11.

I have added a bungee cord to the line to absorb the shock of a fish taking the hook. Maybe that will prevent the hook from breaking, and secure the fish next time.

April 10 — Day 19

Well, again something enormous ripped a brand new hook off the end of my line. The loop at the end of the stainless steel leader was still closed, meaning the hook's own loop broke. Apparently the bungee cord couldn't absorb enough shock. I've put on some larger hooks. These big, mysterious fish should make a tasty meal, assuming I bring one in.

The wind is now aft of the beam, for the first time on this crossing. I have dropped the staysail and am running a billowing genoa and a reefed main. I don't need to move East any more — I can relax my sails and sail a more Southerly course. About 7 degrees South I will turn directly to my destination.

These long passages make me optimistic about relationships. At this distance from land I look forward to meeting new people, forming friendships, lasting associations. I suppose it would be more convincing if I showed such optimism on land.

I may be more enamored of the principle than the thing. After all, notwithstanding all my chatter about the fulfillment potential of a relationship, most of my choices reduce my suitability (or availability) for one. I guess I would rather have the unfettered principle than about half the relationships I've experienced.

My life was simpler once. When I panhandled and slept on rooftops, anyone who got involved with me had no obvious ulterior motive. Now the myth of the male provider and the gingerbread cottage permeates all my relations.

My candor makes things worse. I come from a family in which secrets and outright lies did enormous harm, so when I decided what kind of person I would be, I placed frankness high on the list. So when someone asks me what I do for a living, I tell them. Maybe in the interest of cultivating less burdened relationships I'll become a hypocrite and throw out one of my cherished standards — I'll learn to lie. Or maybe the IRS will figure a way to clean me out, and I can resume panhandling and sleeping on rooftops.

April 11 — Day 20

Late last night the wind died, then the squalls began. The wind velocity varied between none and 30 knots. All night long I started and stopped the engine, broke out and struck sails, and was generally miserable. Now I'm way behind on sleep. I am in a relatively normal area right now, but there are cloud buildups fore and aft. I hope I get to approach the Marquesas in a state other than exhaustion — the chance of meeting another boat is greater, and there are outlying islands and reefs.

I am 192 miles from Nuku Hiva now, so if I can keep the speed up I expect landfall within 48 hours. O please let it be a nice couple of days...

There is an incredible number of things that broke on this crossing. I need to rebuild the windmill vane. I need to find and seal some topside leaks (something you have to be out in snotty weather to test). The auto pilot just ripped out one of its mountings — fortunately I have two. But I have to think up something new for that mounting. The genoa needs extensive repair, which may have to wait until Tahiti.

Even though it nearly self-destructed on the way, the genoa was useful on this trip. Most of the time I had to roll it up too far for it to work efficiently, which is why it began to tear, but when the beam and aft winds started a couple of days ago it really began to move this boat. Now I'm averaging over five knots and I saw a reading over six knots when the surface was calmer.

I am now well East of the Marquesas and tonight I am going to start pointing directly, using my satellite navigator full-time as I come close to land.

April 12 — Day 21

It was another snotty night — a succession of big blows, torrential downpours, and calms, meaning I had to be up the entire night adding or reducing sail or starting the engine. Right now it's overcast, the wind is very light, and the sea is high and confused. It's not great weather for an arrival.

I expect to anchor at Nuku Hiva either late tonight or early tomorrow. I will probably have to stay up again to make the landing safely. There's nothing worse than trying to sleep while careening toward a land mass.

April 13 — Day 22

I crossed into Tahiohae Bay at 5:30 AM, so the enroute time was 20 days, 20 hours and change. Quicker than I expected. I am getting ready to go ashore and visit Customs.

I am sure when I've had some sleep the list of repairs won't seem so intimidating. I've added the mainsail top track slide to the list. It must have torn out during one of the squalls.

It's pretty here...

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page

Share This Page